People love the spectacle of a miserable fat person. The ‘unhappy fatty’ is pervasive: from tell-all interviews where a size 14 reality TV star bemoans her cellulite, to hordes of obese people on The Biggest Loser being publicly berated for their weight, to the sneaky beach pics of celebrities with jiggling bellies and touching thighs which a few months later lead to a book deal and insipid exercise DVD. Happiness is for the thin.

But what’s so wrong with being fat?

The answer many people would give is that it’s ‘unhealthy’, but often, that isn’t what they mean, at least when commenting on an individual’s weight rather than the problem of obesity. Of course many people are rightfully concerned about the health of the general population, but when it comes to individuals, what really bothers people about fat – whether or not they admit it to themselves – isn’t that it’s unhealthy. It’s that it’s unsightly. Unappealing. Unattractive. On the whole, we tend not to care much about that guy on the TV’s health unless it negatively affects our viewing pleasure.

Being overweight can be damaging to health; that’s a fact. Another fact is less commonly acknowledged: that it is perfectly possible to be healthy while also being overweight. This, when brought up by the body positivity movement, seems to provoke nothing short of derangement in otherwise sane, rational, open-minded people. ‘What do you mean, fat people can be healthy? Every single fat person without exception is going to rot in an early grave, buried under the rubble of OUR MURDERED NHS.’ Don’t get me wrong, I’ve seen the statistics – excess fat can lead to heart disease, diabetes, etc, etc. But people aren’t statistics, and it makes no sense to treat every single fat person as a representative of the whole.

And isn’t that what people are doing, when they see a plus sized model or a confident fat person showing their body on Instagram and immediately jump on them as ‘promoting an unhealthy body image’ or ‘not taking care of themselves’? There are a vast number of ways that a person could be taking care of themselves that aren’t immediately visible. Maybe they workout more than most but are naturally bigger, or prefer their body with a few ‘extra’ pounds. Maybe they don’t care about how their body looks because they’re busy trying to become a neurosurgeon or write a novel or look after three kids and an ageing parent. Why does it matter? Why do people care so much?

And we can’t deny that people do care, so much. As a culture, we are obsessed with bodies, particularly women’s bodies – although the point I’m making is relevant to all genders, the issue is magnified for women due to the excessive value assigned to their appearance – and particularly with thinness/fatness and the personal worth we assign to people based on their position on that reductive and somewhat arbitrary spectrum.

I say arbitrary, because beauty is subjective. To a larger extent than most of us realise, what we find attractive is learned, not innate. It’s true that in the homogenised culture of the West, we can all roughly agree which people are good looking and which aren’t, but these definitions aren’t consistent across cultures and eras. In the 17th century plump Rubenesque beauty was highly prized (and no one made snarky ‘get on the treadmill’ comments about his muses). In the Elizabethan era, big foreheads were a thing, and women often plucked their hairline back by about an inch to create the illusion of a fivehead (why?). In Arabian society in the Middle Ages, female beauty lay in having a round face; in Japan in the 17th and 18th centuries, female beauty lay in having a long, narrow face.

Two hundred years ago in Britain a tan was about as desirable as a third leg – poor people were tanned because they had to work outdoors, and so paleness signified wealth and nobility. With the rise of the middle class and the invention of air travel, the significance changed: suddenly a tan meant you could afford to go on holiday. Similarly, in poorer countries extra weight equates to extra wealth and is thus seen as a desirable social symbol. Beauty is not only commodified by capitalism, it is defined by it.

And the changes aren’t always separated by centuries or continents. In the 90s, beauty was over-plucked eyebrows and ‘heroin chic’ skeletal thinness. Now, in our post-Delevigne, post-Kardashian world, big butts and heavy eyebrows are the look to emulate, and the sorry teenagers of the 00s are desperately trying to HD Brows their 3 remaining eyebrow hairs.

Now, beauty being a social construct and not some solid, hyper-real thing doesn’t mean it’s easy to disregard. It’s cultural, and that shit is buried deep. Take movies and TV shows as an example. Fat girls are almost never the protagonists; fat girls are almost never the romantic leads. No one pines over fat girls. No one writes songs for fat girls. And average-sized or chubby girls, girls who aren’t Hollywood thin but aren’t overweight either, don’t exist at all.

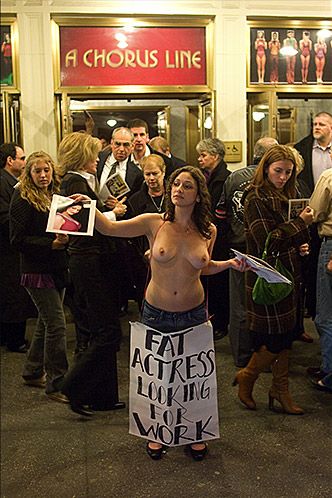

This last point is illustrated best by the anecdote which accompanies this picture.

The actress explains: ‘I had a meeting with a casting director from LA. Without a glance at my headshot or resume, and not even a decent introduction, this stranger looks at me, all 5 feet and 2 inches, 125 pounds of me and says, “You need to lose twenty or gain thirty because where you are right now, I can’t do anything with you.” A bit thrown, but not wanting to be rude, I ask, “Can you elaborate on that?” To which she replied, “Your face says ingénue but it wouldn’t quite work, and I can’t put you as fat best friend because you’re not exactly fat.”’

In our shared cultural imagination, fat girls and ‘not exactly fat’ girls are not ingénues. They do not have – cannot possibly have – the Interesting and Exciting and Quite Possibly Dangerously Thrilling lives that we all lusted after as teenagers. And for teenagers, young people who are just beginning to define themselves and their futures, being able to imagine yourself as the exciting ingénue or the badass lead character is incredibly important.

When I was twelve, I remember inspecting my figure in the mirror critically for the first time and asking my gramma when my stomach would get flatter. When I was thirteen, I bought a padded bra and delighted in the fact that it made the rest of me look thinner by comparison. When my problems with my body really began, I was fourteen years old and perfectly average: 5’7” and a size ten. And I thought that I was fat.

Let me clarify. I knew I wasn’t fat: intellectually I could look at my body and know I wasn’t overweight, and that I was in fact thinner than a lot of people. I was, as that casting director so carefully put it, not exactly fat. But I wasn’t exactly thin thin either. I didn’t look like the girls in the magazines or the movies. I didn’t have a perfectly flat stomach. And so I when I was fifteen, I started a thinspo blog.

Thinspo, to the blessedly uninitiated, is thinspiration: pictures of thin people designed to motivate you to lose weight. I spent hours every day on Tumblr – literally hours – poring over pictures of waifish girls with concave stomachs, protruding hips, knife-sharp collarbones, and thigh gaps wider than their actual thighs. As someone with wide hips and big boobs, I was never going to look like those girls no matter how much I dieted.

But oh, how I longed to. Really. I pined. I looked at these girls with the yearning desire of a long distance lover. These girls were a wish and a promise: that I too could be as beautiful, as beguiling, as effortlessly chic as them if only I had the willpower to become Thin Me. The temporally distant but oh-so-alluring Thin Me was not only physically improved, oh no: she was bestowed with all the confidence, charm and grace that her suave new look must surely foster – as though confidence, charm and grace could only manifest inside skin stretched tautly over bone.

I took action too: I eagerly collected diets I had no way of following while living with family; I counted calories occasionally; I avoided food all day only to binge on biscuits later; I calculated with mathematical precision exactly what weight I’d be on a specific date if I ate x amount of calories per day; I spent a feverish month going running every night in sub zero temperatures; I bought diet pills on the internet; I toyed with making myself throw up. But mostly, I looked at these skinny girls for hours and then I looked at myself, and that was the worst thing of all.

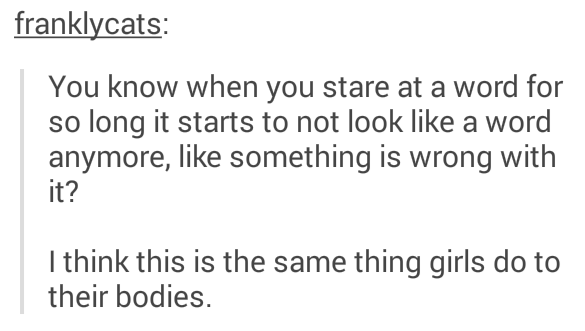

Ironically, it was on Tumblr that someone finally articulated what my thinspo Tumblr did to me, what happens when you subject your body to such intense scrutiny:

My body wasn’t bad, but it felt all wrong: I felt uncomfortable in my own skin, uncomfortable in my clothes, and incredibly self-conscious almost all the time. I yearned to ‘be able’ to wear whatever I wanted, as though I was physically incapable of donning a crop top – as though the world would implode if I dared to wear a bodycon dress without first starving off my podgy belly.

I was never diagnosed with an eating disorder, and I don’t particularly consider myself to have had one. My behaviours around and attitude towards food were pretty fucked up at times, but many of my friends went through similar stages falling under the broad headings of ‘being weird about food’ and ‘quietly hating yourself’. When, at eighteen, I confessed my secret thinspo blog to my best friend, she excitedly admitted that she had one too. I recognised her blog name. Hell is a teenage girl.

Self-hatred is the logical conclusion in a world saturated with photoshopped perfection. Consciously unlearning our self-hatred is a damn sight harder than subliminally learning it, but it can be done. I gave my thinspo blog up a long time ago, but held on to some tenuous link with the idealised Thin Me of the Future by following fitspo instead, rationalising it as healthier, motivating, good for the soul; in the end – for me at least – it was just more of the same.

Now, the only bodies I admire on the internet are those of the women of the body positivity movement, who come in all shapes and sizes and often a range of exciting hair colours, like the Barbies we were never taught to dream of but so desperately need. My Instagram feed is full of women showing off their podgy stomachs and big thighs proudly – all the things I was so incredibly ashamed of having – and that has helped me see myself, finally, as I actually am: totally fine.

So when people say that that the inclusion of ‘plus-sized’ models and actors on the catwalk and in films and magazines is harming us, that the body positivity movement is ‘promoting an unhealthy body image’, I want to scream. The body positivity movement didn’t create my unhealthy relationship with food and my own body. The body positivity movement doesn’t fuel the eating disorders which have the highest mortality rates of any mental illness. And we didn’t reach a point where more than half the population of the UK is overweight due to fat people being accurately represented in the media.

I agree that if increased representation of chubby and fat bodies on our screens resulted in humanity flocking en masse to their nearest McDonalds to stuff their faces in the hopes of being the next Tess Holliday, that would be a bad thing. But that’s not what putting ‘plus-sized’ people in magazines and films and on runways is going to do, even if they are as big as size-22 Tess. All it will do is create a comparatively tiny push back against the hulking giant of the entire Western culture and media that tells us that women over a size 8 aren’t worthy of our attention. Hopefully, it will help the next generation of teenagers (and current adults!) to escape the self-hatred which is, unequivocally, the unhealthiest thing of all.

Eating disorders affect around 7% of people in the UK, a quarter of whom are male – but these figures don’t reflect the real impact of our obsession with our bodies, because being ‘weird about food and quietly hating yourself’ isn’t necessarily qualified as an eating disorder. Much more telling are the statistics that state ‘50% of teenage girls and 30% of teenage boys use unhealthy weight control methods such as skipping meals, fasting, smoking cigarettes, vomiting, and taking laxatives’. 80% of ten year old girls in America have been on a diet. More than 50% of women see a distorted image of themselves in the mirror. Yes, sometimes, fat is unhealthy. But it’s a damn sight healthier than our cultural obsession with thinness.

Mental health is health too.

Ten years after I first asked my gramma when my stomach would be flat, I do not have a flat stomach. As I write this, I’m sitting in my bra looking down at the little roll of pudge poking over the top of my jeans. This pudge used to mean that I was a failure, destined for an unremarkable, mediocre life. I would never be the cool girl, or the hot girl, or the girl someone falls in love with.

My pudge doesn’t mean that any more. My pudge exists because of all the times I ate pizza in bed with my boyfriend, or ate a bunch of snacks while marathoning Lord of the Rings, and I fucking love those times. And I can be hot and cool and loved. It was never the pudge that was stopping me – only my anxious teenage brain and what our body-obsessed culture did to it.

That’s why the body positivity movement is not only important, but essential: it teaches us that in a world where flaws are unforgivable, we don’t have to forgive ourselves. There was never anything to forgive.

by Lauren Jack

I was bullied for a lot of my adolescence for my tallness, big nose, un-sightly dark body hair on my arms, my legs, anywhere. I was grown up to feel alienated, too weird to belong, not quite right enough. I carried on to feel this way right up until I was 18, and then I had an enlightening experience. I went to Greece and in the small town the majority of women looked just like me, dark hair, large nose, tall and I realised this was the norm here and this was attractive, I was so overjoyed. Just the slightest change in what was acceptable and attractive in society meant that I no longer felt weird and out of place, I knew that although there were people that would tell me I was unattractive flat out there would also be people that would say I was extremely attractive. It taught me that beauty isnt a definitive goal. It empowered me to shove my big nose in people face, grow my hair on my arms and legs as dark as ever and fuck them if they say anything because it’s not my problem.

Me parece genial el articulo!!!!!!!!!!