Written By: Arianne Crainie

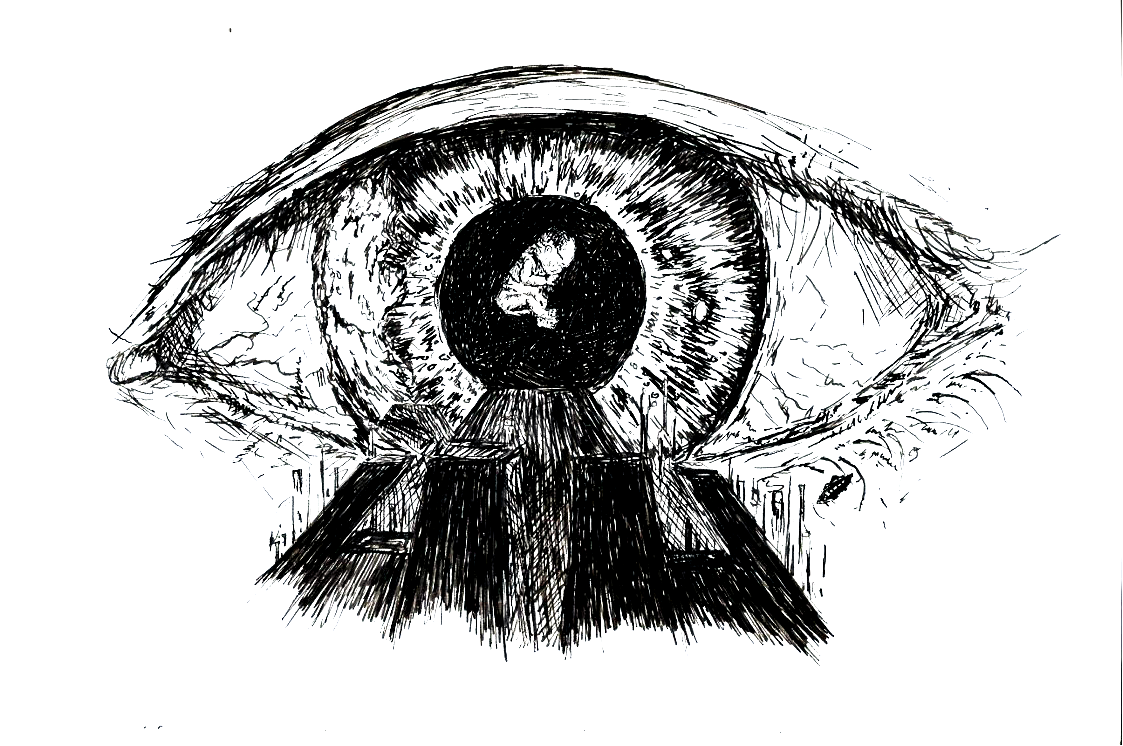

Illustration: Michael Paget

Warning! Spoilers ahead!

Thirty-five years ago Ridley Scott’s cult classic Blade Runner illuminated the big screen with questions on modernity, humanity and identity. Now its offspring, Blade Runner 2049 dir. Dennis Villeneuve, is updating these ideas to run with our contemporary society. Or at least it tries to.

Throughout Blade Runner 2049’s behemoth running time (nearly three hours) I was tempted to copy the viewer in front of me and fall asleep. The film mirrors many of its primary motifs. It’s a stunning, empty copy of the original – a hollow simulation that doesn’t quite hit the mark. It looks and sounds like its predecessor in many ways: tracing the story of a blade runner on a case who grapples with identity amidst the elusiveness of reality and progress. This time around it’s explicit, instead of suggested, that the Kafkaesque detective/assassin K is an android himself. Presumably this is intended to up the heat and bring the film’s recurring themes to boil. Nonetheless, whilst appetising, the film lacks some crucial ingredients.

For one Blade Runner 2049 is saturated with sweeping, aerial views of dystopian L.A. and its gargantuan architecture. Despite their gorgeousness, these eye-in-the-sky shots fail to capture the subtle, lonely beauty of cosmopolitan living. The first film did this most notably with the footnote of a scene in which the camera pans from villains Roy and Leon to capture a sudden rush of cyclists, backlit by the neon-drenched city. In these seconds the audience is permitted to see and feel the warmth in an otherwise vacuous metropolis. By omitting such scenes, Blade Runner 2049 sacrifices whatever “humanity” it intends to reveal. This is the films main problem: it attempts to swirl blockbuster visuals, neo-noir tropes and hints of philosophy without fully sketching anything out.

Lack of follow-through is also seen in its approach to thematic concerns. As with Blade Runner, wealth inequality, misogyny and colonialism are mentioned or depicted. Nevertheless, the sequel fails to objectively frame these issues. In the original, the whiteness of spacious and lofty corporate towers contrasts with the cramped, multicultural streets and is offset by blaring advertisements for off-world colonies, available only to the rich: an unjust yet believable representation. The sequel merely throws in the word “colonial” a few times and features POC in a number of (forgettable) roles that often feel like diversity for diversity’s sake.

Similarly, female characters are under-utilised. Whilst their desires go unfulfilled, K is catered to by hologram housewife and customisable fantasy Joi. This could’ve been a good opportunity to delve deeper into the ethics of virtual wives, whether this is pure misogyny or a side effect of alienation within a capitalist patriarchy. Instead, the film opts for a one-sided argument, presenting K as a stoic, noble hero whose motivations go unquestioned. This misbalanced perspective is rooted in the films foundation. Blade Runner 2049 is built upon the retroactively applied grand romance of Deckard and Rachel. I found this particularly hard to engage with because of the “love scene” of the first film, where Deckard prevents Rachel from leaving by slamming her against the window and commanding her to say that she wants him. In my opinion, this was how the original film confronted misogyny. By depicting Deckard’s dismissive and violent behaviours, it postulated how the colonial, sexist values of a society can manifest themselves within an individual. And so, by glossing over the discomfort of its predecessor with a rose-tinted sentimentality, Blade Runner 2049 can’t really claim to be justified in its portrayal of women.

Blade Runner 2049 struck me as being so close but yet so far. The sparks of poignancy that characterised the first film are few and spread too thin. It has stunning aesthetics but lacks nuance and has intriguing yet under-developed ideas. Granted, there are some beautiful scenes that ponder the nature of free will and memory. But ultimately, all these moments are lost, sandwiched in between explosive fight scenes and what feels like hours of Ryan Gosling staring at nothing. That being said these are all my own personal views and, to answer one of the films questions, variety is a vital component of humanity. So why not go see it for yourself?

Your illustrator has got it exactly right 🙂