Glasgow University Magazine

SEEING RED

EDITOR’S NOTE

Shuffle the deck. What once-in-a-lifetime crisis would you like today? You might think we’d be fast running out of options but the twenty-first century seems to be developing an impressively relentless nature. Global pandemic? Old news. Generational cost of living crisis? Standard stuff. Studying in a city with a student housing catastrophe? Been there. The last few years have been quite the ride – that apocalyptic shopping list providing just a taster menu of discontent. A few honourable mentions should also go to to unprecedented rollbacks of reproductive rights in the USA, a UK government that seemed to be admirably intent on pursuing economic armageddon (yes, that’s you, Liz), and, of course, the small matter of the increasingly obvious and frightening climate emergency. But hey, maybe this is just what growing up feels like.

SEEING RED is rejection of passivity. Embrace action in whatever form it comes. Rave all night to one-hundred-and- eighty BPM hardcore. Ink a soon-to-be-forgotten lovers’ name across your chest. Buy a new lipstick – you’ll feel better for it (it says so on page 29). We, as young people, are not merely passive victims in an unfair world but active and expressive agents of our own destiny.

We’re told that getting angry won’t help anything. But, this is us giving it a go regardless.

Lots of love,

Ava + Conal xxx

CONTENTS

FEATURES

KEEPING ANGER IN MY BAG

Isobel Dyson

4

LOOKING BACK IN ANGER

Soumia Serhani

6

CULTURE

RIGHT PLACE RIGHT TIME: GLASGOW’S HARDCORE RENAISSANCE

Kate McMahon

8

INCLUSIVITY AND IGNORANCE AT THE BURRELL COLLECTION

Luisa Hahn

10

THE COST OF LIVING CRISIS THROUGH THE EYES OF YOUNG CREATIVES

Robert Goodall

12

POLITICS

RED RIGHT HAND: NORTHERN IRELAND’S GROWING REJECTION OF BRITAIN

Alex Agar

14

A RED FLAG RISING: WHAT TO MAKE OF

THE RETURN OF THE WORKING CLASS

Ellen Ode

16

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT

IN CONVERSATION WITH ZOE KRAVVARITI 18

STYLE & BEAUTY

BRANDED FOR YOUR PLEASURE E.B

26

THE LIPSTICK EFFECT: WHY WE’LL BUY A NEW LIPPY BUT NOT TURN THE HEATING ON

Kathleen Lodge

28

PUNKS AESTHETIC LEGACY: I KNOW WHAT I WANT AND I KNOW HOW TO GET IT

George Browne

30

SCIENCE & TECH

THE INFURIATING COST OF ENTRY TO THE BOYS’ CLUB

Sytske Lub

32

BEHIND RED ZONES

Amelia Coutts

34

CREATIVE WRITING

LITTLE RED

Kitty Rose

36

A SCARLET LETTER, AND CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES

Paul Friedrich

38

KEEPING ANGER IN MY BAG

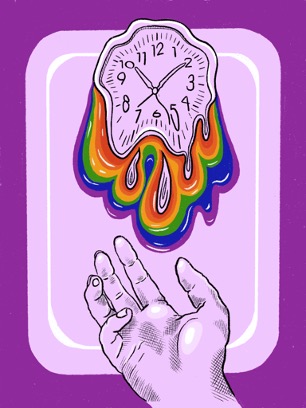

Words: Isobel Dyson (She/Her) Artwork: Joanna Stawnicka (She/Her)

TW: Spiking

The number 251 is written in silver marker on a piece of cardboard sitting in the middle of my little pouch bag that contains way too many, mostly unnecessary cards. My brother recently, in a fit of exasperation after I had taken embarrassingly long to find my ID, sorted out my cards for me. Five useful cards on one side of the piece of cardboard, five hundred very un-useful cards on the other. The, now useful, piece of cardboard entered my little pouch bag on a night out in Wrocław a few months ago when I was working in Poland. My coat had been the 251st coat I suppose.

Six months later that cardboard is still there and, thanks to my brother, helping me easily whip out my bank card as I pay for two beers. I’m at a music festival with my music loving father enjoying the unusually hot summer sun in Nottingham. I weave my way through glittering, wiggling bodies trying to remember where I’d left my dad, beer cooling my hands as I unsuccessfully avoid flying limbs. I spot him fairly close to the front and hand him his beer. ‘Ocean Colour Scene’ are next. My dad assures me they were very popular around the time I was born. Being unable to add anything interesting to this fact I sip my beer and watch as a group of white haired men walk on stage. They’ve bagged a good time slot. The crowd is at a peak level of jolliness and greets the band with much enthusiasm. No introductory chitchat, they launch straight into the first song. Not bad, I think, although I was in a good mood and consequently not very fussy. Unfortunately the band’s good start was very brief. ‘Something’s gone wrong with Steve’s guitar’ the lead singer announces. They get ushered off stage and are replaced by two technicians. But less than ten minutes later the band returned to raucous cheers.

However, the technicians are still kneeling on the stage working miracles on some cables. The guitarist marches over and kicks the technician from behind. That’s right, he kicked the guy bent over, fixing his problem. I turned to my dad in disbelief. He was doing the same to me and said, ‘Did he just kick that guy?’. The crowd hadn’t reacted but we had both seen it. He then stepped forward and lifted his shirt up showing off his chest. If you played this band to me now I would not recognise it. The rest of their set I spent staring daggers at this man. I cannot tell you for sure whether or not the kick actually made contact but to me it doesn’t matter. What he did was so degrading and humiliating and he did it in front of thousands of people to someone who is essential to him being able to play. This was not a poorly executed joke.

I watched him throughout their gig and he continued to act aggressively the whole way through and as I was watching him I began to feel jealous. How can this man have so much anger, act on it so viscerally and inappropriately and still be cheered on by thousands of people?

I, on the other hand, struggle to feel anger. I rationalise, justify and see the other side of things until anger doesn’t have a space in my head.

But some things can’t be rationalised or justified and then what happens? How do I cope with that? Kick someone? Anger is a bad thing, right? Well, that’s what I have always thought. That night out in Wrocław – when I acquired that little piece of cardboard – my drink was spiked. My two friends and I entered what I would classify as a ‘high quality cool’ club. A bit grunge-y, weird looking people, my kind of jam. We handed over our coats and she’d run out of number tags so she just wrote 251 in silver marker on a card for me, which I stuffed into my little pouch bag. I met some people by the toilets, as you do. I said, ‘Come let’s get a drink. You can meet my friends’ and I don’t remember much after that.

I was lucky I had two guardians by my side who sat with me while I floated through space with my head between my knees. They sat with me while some man came outside and tried to convince them to go back in and dance. They sat with me while the uber found another customer because I couldn’t stand. They sat with me while I threw up everything in my stomach and splattered my shoes with sick. They held me, one on each side, when I could finally walk home while I cried uncontrollably. They undressed me and put me into bed where I slept safely but with bizarre dreams. The next morning I felt like someone else had taken over my body for the night and I was filled with rage, like my blood turned to lava. Who thinks they have the right or the power to do that to someone else? I felt like a puppet in someone else’s game.

I keep that piece of cardboard in my little pouch bag because it always makes me angry and reminds me I have a right to be. I know that growing up as a girl has made me censor this emotion. I constantly catch myself trying to smooth over awkward situations, laughing at jokes that aren’t funny, shutting up when I get interrupted. I do it unconsciously even now when I’ve made myself aware of it. I keep that cardboard with me because it gives me the strength of anger to push back and stand my ground. I’m learning to let anger fuel me and live with me rather than be something that I only feel once in a while. I just won’t kick anyone because of it.

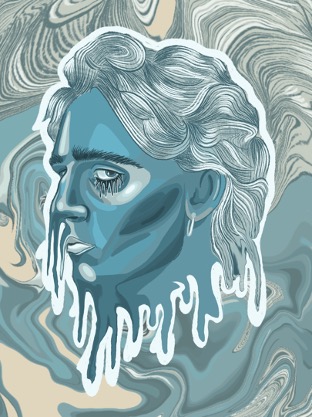

LOOKING BACK IN ANGER

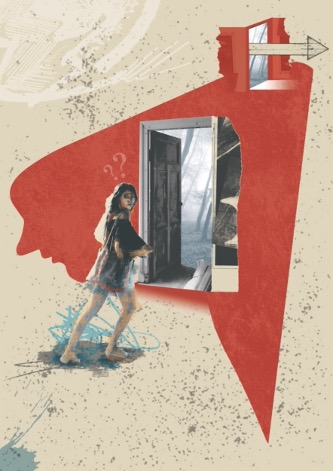

Words: Soumia Serhani (She/Her) Artwork: Leotie Whitelaw (She/They)

When I was younger, around the age of 9, I wore a hijab and a jellabiya outside for the first time. I thought the dress was beautiful and I loved the hijab because it had pink gem detailing on the side, and it made me feel strong and connected to a side of me that I never fully got to embrace in my small town in Scotland. I think I went to the cinema. I do not remember the exact details of the day, but I remember the feelings.

I have never been stared at like that in all my life. It was as if I was an animal or an attraction of some kind for uneducated eyes to crucify what they could not understand. I had never felt so exposed, despite being so covered up.

Upon reflection now, I think I have received less attention for having more of my body on show than I did at the age of 9 for dressing with modesty. I have never felt shame like I did that day. I had to face the accusing eyes of old men as they scowled and scoffed at me simply for what I had chosen to wear – for what had made me happy. I had to walk past tutting women who didn’t like what they saw and wanted to make it known. I remember trying to keep my head up, but I regretted my choice within ten minutes of leaving the house. That’s all it took.

One day of judgement and I never wore one again – not even in my own house. I wonder how different my relationship with my culture would be now if my home country had not shut me down at the first sign of expressive difference. What if they had opened their minds to anything other than the pre-accepted norm? Would I feel more in touch with my own culture and my beliefs? Would I wear a hijab now? I cannot be certain. I am certain, however, that I carry the shame I felt for having the audacity to try to challenge the attitudes that were fixed long before I was born. That because I lived in a White, Christian country, I would try to appear as close to a depiction of a White Christian as possible. That I would not challenge these ideals by wearing something associated with Islam.

I remember feeling guilt because I was out with my family, and I thought this would make them targets for menacing eyes as well. I was so embarrassed. I felt shame and mortification searing through the material of my dress to the point that I wanted to cry and take it off. It was only one day. I had one day to try on a potential new me that may have changed my life.

There are so many people, institutions, and structures that I want to blame. I want to scream about how this country is so backwards that it made me feel ashamed at the age of 9 for wearing a long dress and a headscarf. I want to cry because this shame has stayed with me for my entire life, and even knowing now that these people who shamed me simply did not have the capacity to understand, brings me no relief. It was snatched away from me by people who did not even have to speak their words to announce their hatred – but felt more than comfortable expressing it through their piercing gaze. I repressed this memory. It only came back to me recently when I tried a hijab on again, for the first time in a long time.

Upon remembering, I felt sick to my stomach, like I was experiencing it all over again. I will never shake these feelings – they are so deeply embedded into me.

I am angry and I am hurt at the unfairness and injustice of it all. It’s not a crime to give someone a dirty look, but it is also not a crime to wear a hijab. I want to embrace this anger – I want to feel rage and I want to feel it deeply. I want to feel so angry that it absorbs all the sadness I feel. I want to fight, so that the next young girl that wants to try a hijab on, never has to feel the way I was made to feel.

I am taking my anger and my hurt and I am using it to make a difference. I have the capability within myself to take this pain and turn into something bigger than myself. I am not the first person to feel this, and I certainly won’t be the last. I hope that by sharing my story, I can make someone think twice before passing someone a judgmental look on the street – no matter what they are wearing. We need to believe that our words of anger have power.

Right Place, Right Time: Glasgow’s Hardcore Renaissance

Words: Kate McMahon (She/Her) Artwork: Lewis Aitken (He/Him)

I’m breathless, leant with my back against the wall. Frontlines of my sweat advance towards the stew of condensation lining the club walls, forming a half-warm half-heavy dew. I roll my head, watching a curtain of fists sweep across the floor, beating in unity to the thump, thump, thump of nightcore. Cries of distorted wobs wrestle against a pounding bassline.

It’s a sound that hits you across the face, breaks your nose and carries on punching. All the while, pink strobe lights and images of anime girls project around the room as strangers in animal ears politely compliment each other’s outfits. This is Fast Muzik and it’s the happiest I’ve ever been. It’s difficult to describe the attraction of a hardcore club night to someone who’s never been to one. But with both of Glasgow’s hardest hitters, Fast Muzik (@fast.muzik) and Mutt Klub (@muttklub), consistently selling out, it’s clear that the subculture is capturing something within the city’s zeitgeist. The popularity of Fast Muzik, Mutt Klub and recent hardcore force majeure Bloodsport (@x.bloodsport.x) could be attributed to the gut-punching bass or the stompy interludes of pop nostalgia, but the traction of these nights doesn’t begin nor end with the music.

Inclusivity is woven into the very fabric of Glasgow’s hardcore scene. These respective nights share a manifesto of ensuring a safe space for everybody. Bloodsport labels itself as a night where ‘all are welcome but queer people are more welcome’ and Mutt Klub ask their followers to educate themselves ‘on the dangers posed to LGBTQ+ and POC communities that necessitate a safe space policy’.

The line-ups for such events reflect this ethos of inclusion, with the scene offering opportunities for DJs from several marginalised communities. While Glasgow hosts some of Scotland’s most varied and vibrant parties, representation in dance music is still often overlooked, and even in this subculture-rich city, progress needs to be made. In 2019, 81% of artists booked for UK dance festivals were male, with 18% being female and only 0.5% identifying as trans.

Meanwhile, 77% of artists were white, yet POC performers only comprised 23% of bookings. It’s blindingly obvious that dance music is still sidestepping huge swathes of society. Although line-ups for major dance festivals have become slightly more inclusive since 2019, there is still a lack of inclusion of trans and POC DJs.

It doesn’t take a psychology degree to understand the power of role models – Glasgow’s kids seeing themselves in a hardcore line-up won’t just be a source of personal strength but will shape the city’s dance music scene for years to come. The dance floor has, historically, for LGBTQ+, QTIPOC, and gender-diverse communities, long been an arena for escapism and ecstasy. A life can be lived, drank, and danced within a single night in a sweaty room, separate from the dreary day-to-day slog. With successive governments failing to protect the rights of these communities, exclusionary policies, and a general feeling that the higher-ups just don’t care, these spaces are still as vital in 2022 as they were decades ago. It’s not just about having someplace to go on a Friday night. It’s a time to share stories with a friend you didn’t even know you had. It’s a place to wear that outfit you always wanted to try but never dared and a venue to spark change outside the monoliths of work and education.

Ascending the club’s stairs after the final steel pulse circuits your entire being, you look back on a night that was free from judgement, policing and a smart casual dress code. A night where you are able to say ‘this is ours’. That is true power, and it can’t be taken away.

It may come as a shock that a genre so gutsy, brawny and ballsy is championing Glasgow’s marginalised communities, but hardcore has always been a melting pot for stewing rage. Look no further than its birth in late 80s Europe and growth in the wombs of small towns in post-Thatcherite Britain; the genre’s presence at illegal raves, a remedied antidote to the status quo. The happy hardcore heavyweight Fast Muzik, with its chopped-up, pitched-up, whizzed-up mixes of My Chemical Romance, The Sugababes and Lady Gaga alongside the omnipresent pounding bassline feels like the perfect vantage point for kids who grew up with the internet for a sibling. A floor full of people with their hands in the air screaming along to a Kylie Minogue remix. It’s transcendental, unpretentious, and part of something bigger than the strangers in the room. Despite what the outside world is saying, in that heaving club, I breathe a sigh of relief.

Finally, I’m in the right place at the right time.

Inclusivity and Ignorance at the Burrell Collection

Words: Luisa Hahn (She/Her) Artwork: Louis Managh (He/Him)

Even if change in Britain’s public gallery and museum sector is still a slow game, the expectations to make restitutions for their colonial pasts and include representations of minority-group histories in their exhibitions are rising. It is therefore not surprising that the Burrell Collection, which reopened this year in Glasgow’s Southside, has been a topic of debate. What is surprising, however, is that whilst this debate surrounds the Burrell Collection’s queer-inclusive labelling of some exhibits, it fails to address how many of the Burrell Collection’s artefacts have entered the collection during the height of the British Empire’s brutal rule.

The collection was amassed by Sir William Burrell, who made his fortune in Glasgow’s shipping industry before and during the First World War. He donated his collection to the city of Glasgow in 1944. Burrell, who is often lauded as one of the world’s great art collectors, purchased works by European Modernists, such as Degas and Manet. However, a sizable chunk of the collection is made up of artefacts from around the world, commonly bought in bulk from London auction houses and dealers. The interest in these artefacts was in their ‘exotic’, ‘ancient’, or ‘oriental’, but not their site-specific origins or the circumstances under which they were acquired.

Burrell was not alone in this practice, and British public and private collections, on the whole, are confronted with the task of dealing with the histories they have inherited. Unfortunately, they aren’t doing so – or only to the extent pressure from public discourses forces them to. For collections, it is not only a moral but also a legal and predominantly financial question, whether to return or pay reparations for looted or dubiously bought objects. Whilst many of these objects are of spiritual or cultural importance in their places of origin, they are ‘treasures’ to their Western ‘owners’ and come with large price tags, which British collections are reluctant to give up. In addition to this reluctance, the restitution of looted artefacts is governed by complex legal structures, which collections such as the Burrell Collection hide behind.

Amid the criticism collections are facing over the neglect of their artefact’s bloody histories, it is reasonable to question the authenticity of the actions taken by these same collections aimed at including minority groups in their displays. An example of such action is displayed by the Burrell Collection’s labels, accompanying 2 sculptures of the Buddhist figure Guanyin, who has historically been depicted as genderfluid or transgender. The labels describe Guanyin as a reflection of the historical existence of trans people, stating ‘trans rights are human rights’. Vocal criticism of these labels came from the anti-trans group For Women Scotland. They accuse the Burrell collection of over-politicising the artefacts and pushing a ‘Western viewpoint onto other cultures’. Glasgow Life, which oversees the Burrell Collection, has pushed back on the criticism and defended the labels of the Guanyin sculptures as based on historical research and consultation with trans and non-binary community groups.

The public defence of the labels, as well as a blog post from spring 2021 on the Burrell Collection’s website detailing their efforts to research and include queer histories while consulting local communities, suggests the collection’s investment in giving voices to queer minorities is genuine. However, the same cannot be said for admitting its colonial past. Take the example of a golden disk currently exhibited at the Burrell Collection. Its accompanying label identifies it as part of gold regalia from the Asante Kingdom located in contemporary Ghana. It describes how British soldiers took the Asante gold as part of a punitive raid against the Asante people after winning a violent conflict that emerged along the Gold Coast in West Africa in 1874. Nowhere in the short description is there reference to this manner of acquiring objects as problematic. The label also omits that the director of the London V&A, which is in possession of the bulk of the Asante ‘treasure’, is currently in negotiations with the Asante King and representatives of the Ghanese government over the future of the objects (the most likely outcome being a long-term loan, as the aforementioned legalities prevent a straightforward return).

If the Burrell Collection took their imperial legacy seriously, they would inform visitors on both the full histories of their objects as well as the current status of returns and reparations. As it stands, they remain quiet. Amidst this silence, even their well-intended inclusion of queer history remains meaningless as they fail to understand and address the intersectional dimensions of repression. This lack of intersectionality is reflected well by a corner of the building where the new gender-neutral stalls are adjacent to a plaque reading ‘The Burrell Collection opened by Her Majesty the Queen on 21st October 1983’. The gender-neutral toilets prove their intentions to include certain minority groups, but the plaque reminds us of close and lasting ties with imperial colonialism.

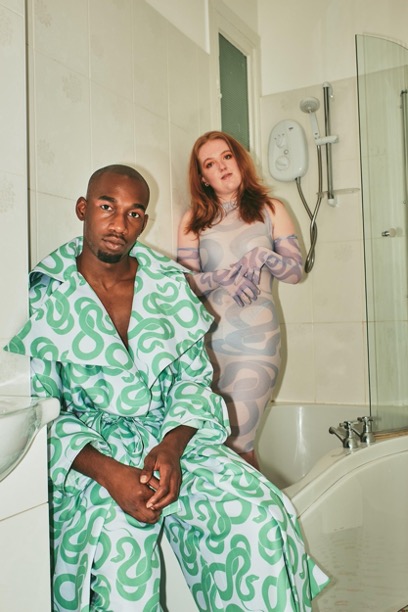

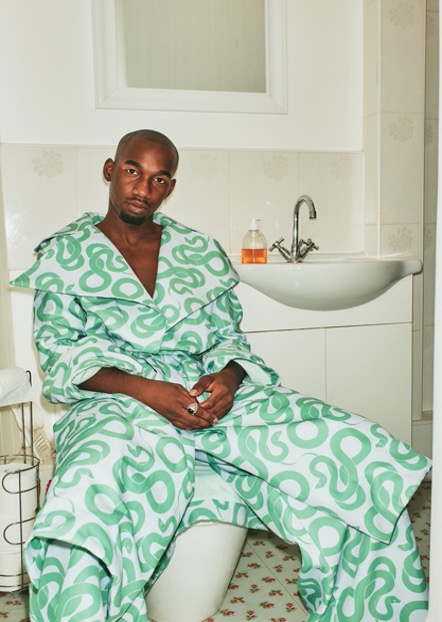

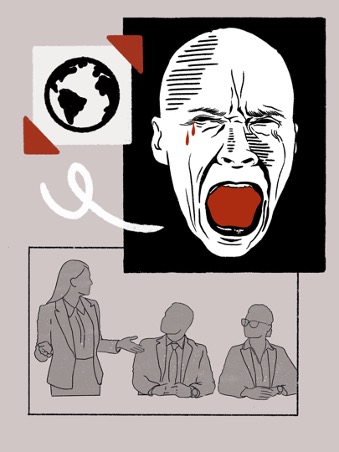

The Cost of Living Crisis Through The Eyes of Young Creatives

Words: Robert Goodall (He/Him) Artwork: Ben Woodcock: (He/Him)

By now, as a resident of Glasgow, it must be nearly impossible not to have heard about the ever-looming cost of living crisis. The crisis constantly comes to the forefront of our everyday conversation, but often in a relatively superficial way, be it through disengaged politicians or worried family members checking in on gas and electricity meters. Despite this, as young students, it can be difficult to really understand the issue presented to us by the media. Many of us are financially sheltered by loans and SAAS, which will help us weather the storm, and perhaps not feel the impacts as acutely. This will not be the case for all students, however. In such a turbulent time, it is important to look at our community and ask how this impacts us.

Recently, I attended Anam Creative’s (@anamcreative) Hot Glue 02 event, which took place near the end of September. I spoke to the organisers, artists, and attendees to gauge the consensus surrounding the cost of living crisis and how this might affect Glasgow’s creative scene in the coming months. Anam Creative is a local collective providing paid interdisciplinary collaboration for emerging creatives in Glasgow. The founder, Michiel, initially started collaborating remotely with musicians during lockdown. The collective has only grown since then, attracting several like-minded people to the group. A significant and decisive milestone for Anam Creative was securing funding from Creative Scotland, a government agency which provides financial aid to Scotland’s creative industries. It is crucial for agencies like this to exist, particularly in the uncertain times we find ourselves in. The funding has enabled the group to organise events such as Hot Glue 02.

Both Michiel and Lily – another organiser of this event – stressed that they were slightly apprehensive due to the ticket prices for Hot Glue 02 being higher than that of their previous projects. This decision was made due to the company’s ethos of paying its artists fairly. In spite of this, the event completely sold out. The room was packed. The crowd proved fluid, adapting to the changing performances and providing a welcoming atmosphere to the performers themselves. Three unique musicians took to the stage: Terra Kin (@terra__kin) supplied intimate, soulful guitar and vocals, NooVision led by Noushy @noushy__ performed genre-bending jazz, and Rory Green (@rorygreen_) finished the night with some ambient, danceable electronic music. The sonic experience was enhanced with liquid visuals from Niki Cardoso Zaupa (@_moventia), which morphed as the vibe shifted from one musician to the next. It was a night brimming with creative energy and gave me a great deal of hope and optimism for the future of Glasgow’s cultural scene.

The fact that this performance was sold out and met with a great deal of support reveals a desire for grassroots creative events like this. For events like Hot Glue 02 to take place, they need our help, and with the cost of living crisis bringing widespread uncertainty, this is even more significant. From speaking to a few of the attendees, it was clear there was a broad mix of people in the crowd, from friends of the performers to regulars of Anam Creative’s events, as well as people entirely outwith the art scene, in search of a good night.

The success of the evening, regardless of the unprecedented times we are facing, showed that Glasgow’s DIY creative scene is robust and prepared to take on the challenges of the cost of living crisis. Michiel and Lily, who look optimistically at the city’s post-lockdown cultural scene, shed a comforting light on how people are valuing and being more selective with their time.

This, therefore, begs the question: what can we do to keep Glasgow’s cultural scene flourishing? Well, we must first push to support and publicise events such as these which are fortunately still taking place in the city. The least we can do is spread the message, ensuring independent performers and organisers persevere. This city is filled with students; we alone will always find a way to enjoy music and art in some shape or form. I would also suggest that the next time you’re thinking of what to do on a Friday or Saturday night, search about, be curious, and support the smaller emerging creatives. There might be something around the corner which will allow you to help Glasgow’s creative scene.

Red Right Hand: Northern Ireland’s growing rejection of Britain

Words: Alex Agar (She/Her) Artwork: Sophie Aicken (She/Her)

CW: Abortion

The term ‘Red Right Hand’ has many meanings. In literature, it is shown in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, depicted through Lucifer defying God and aiming to seek vengeance. Within Northern Ireland, it is depicted on the Ulster flag that has been entrenched in Protestant/Unionist identity to represent the North’s ties to Britain, and thereby in the 30-year conflict known as the ‘Troubles’. Having been born and raised in Belfast for nearly 19 years, in a community plagued by the legacy of this bloody conflict, I am well accustomed to the repercussions of those 30 years of violence. Whilst this period created a perseverance and strength among its people that I am extremely proud to come from, the scars are clear, in the physical and in the political, and has kept my country in the ‘dark-ages’ ever since. You don’t have to look hard to notice that Northern Ireland has been left behind and ignored by the supposed ‘union’ with England, Scotland and Wales, leaving many feeling betrayed and disillusioned, and much like in Milton’s Paradise Lost, seeking retribution through the defiance of a power that has abandoned them.

To quote Dublin-born writer Iris Murdoch, “I think being a woman is like being Irish… Everyone says you’re important and nice, but you take second place all the time.” This idea of being a second-class citizen is not new to women from Northern Ireland. Abortion was decriminalised in Northern Ireland in 2019 by Westminster, following the failure of the Northern Irish government in being restored after two-years of collapse. However, what is seldom known is that – whilst abortion is now legal – there are next to no resources within the country. This means women still must travel to England, Scotland and Wales to receive one, or alternatively use life-threatening contraceptive methods. Whilst we rightfully saw mass uproar within the UK after the overturning of Roe v. Wade in America, what the press and politicians failed to do was acknowledge those in the UK already being let down by Westminster, who failed to publicly condemn or put pressure on Stormont when intervention was needed.

Whilst dangerous, this ‘laissez faire’ attitude towards Northern Irish affairs is not an uncommon approach for Westminster to take. Brexit most notably has caused renewed tensions within Northern Ireland and its fragile peace, with polls showing 56% of the population voting to remain in the EU. In a country as divided as Northern Ireland, both sides could agree on one thing; this was a careless move that would destroy what the peace that had been achieved by such endless sacrifices. Predictably, the passing of Brexit led to extreme violence in some areas as recently as April 2021 by loyalist unionists who felt under threat by the Northern Ireland Protocol, which economically distances the North from the rest of the UK. Police described this series of events as “the worst Belfast has seen in years”, with over 50 police officers being injured, violence being enacted against Catholic communities, and petrol bombs being thrown with numerous buses being set alight. Whilst this was our reality for just over a week, coverage was sparse within the rest of the UK, fuelled by the continuing indifference of the Westminster government. Brexit, whilst infuriating for many, displayed Westminster’s disregard for their ‘allies’ in Northern Ireland, leaving many to step away from the British government towards a more violent alternative.

All of this culminated in the recent 2022 Northern Ireland Assembly election, sending shock waves throughout the country. For the first time since the Northern Ireland Assembly was created in 1998, the biggest Irish nationalist/republican party, Sinn Féin, won by a majority. This victory has been attributed to many things, but most notably a shared rejection of Westminster and a desire within many to leave the union and join in a united Ireland. This was reinforced by the 2021 census, where recent results showed 37.3% identifying as Protestant and 42.3% identifying as Catholic. Furthermore, 31.86% identified as British only whilst 29.13% identified as Irish only. For a country that was created with a Protestant, Unionist majority to ensure loyalty to Britain, these results create serious ramifications within the UK and Westminster. Citizens in 1 of its 3 devolved nations no longer see their place in a Britain still yearning for a return to Empire. This may be a surprise for some, but for many within Northern Ireland, a change of tide has been on the horizon for years. A political vacuum has now been created in which people are looking for solace from a power that has repeatedly let them down. While nationalists have long fought for a united Ireland, it is evident that Westminster’s continued disregard for unionists, through taking for granted their support before Brexit, has made allies into enemies, and allowed for an increase in animosity amongst a group of people which the security of the union depends on.

A Red Flag Rising: what to make of the return of the working class

Words: Ellen Ode Artwork: Louis Managh

People are pissed off. There is no end in sight to the cost of living crisis, and the movement Enough is Enough has gained over 450,000 supporters since its launch in August as a result. The initiative is demanding pay raises, and an end to food poverty and housing for all, while industrial action is currently taking place within a wide range of industries. Contrary to the predictions of politicians and the tabloids, public support of them remains reasonably high, with RMT General Secretary Mick Lynch recently declaring in a rousing speech: ‘The working class is back!’ Anger lies at the centre of it all: people are sick and tired of being poor, and they have channelled this fury into demands for change. A previously slumbering class consciousness seems to have been revitalised.

Perhaps what is most striking about the current crisis is the sense that very few are not affected at all. While working class people, and especially working class people from an ethnic minority background, will face the most significant hardship, a large portion of the middle class will also be feeling the squeeze. Perhaps these shared struggles represent a possibility for greater solidarity and unification of the class groups, challenging perceptions that their views and concerns are diametrically opposed.

You would think Labour, supposedly the party of working people, would be keen to capitalise on this recent advancement of solidarity. Yet it seems that the current leadership believes that these new working class social movements are incompatible with an assumption of power. Indeed, Sir Keir Starmer has disciplined MPs seen to be supportive of rail strikes. While it is troubling that the Labour Party seems to have fallen so far away from its roots, perhaps it is simply no longer the case that mainstream politics, in the UK at least, can facilitate radical social justice. And yet the danger of the removal of mainstream politics from any degree of class analysis is the ability of far-right and fascist movements to occupy this space instead. The far-right, too, will try to address the cost of living crisis, but through a narrative of anti-immigrant sentiment, through which progressive politics are seen as the cause of, rather than the solution to, the crisis. But the dehumanising portrayal of immigrants and ethnic minorities as ‘the other’ has never been a convincing explanation for social injustice, because class is still fundamental. Marginalised groups disproportionately having to take on jobs with terrible working conditions and low wages; big corporations refusing to pay their workers properly; governments insisting on tax cuts for the wealthy while welfare budgets are slashed: it all lies within the same realm. A newfound class consciousness could therefore represent an antidote to the threat of fascism. Finding a new narrative and a vision for the future firmly anchored in socialist and social democratic ideology poses an opportunity for real change and more productive politics while changing people’s perception of where their predicament stems from.

Nonetheless, the notion of returning to the roots of socialist ideology and historical fights for the working class can easily give off the idea of the working class as being white, cis-male, middle-aged and heterosexual. Indeed, in the recent Swedish elections, the socialist group, The Left Party, chose to adhere to an election strategy focused on gaining ‘traditional voters’ in industrial towns, overlooking topics such as climate change. They consequently performed much worse than in the previous election. This patronising and dated portrayal of the working class is detrimental to social justice. The working class of today is, and has frankly always been a dynamic group. It consists of an array of voices, all eager to be heard and all with valuable contributions to make. So if the left of mainstream politics is to fully actualise its supposed aims of facilitating social justice for all, it would adopt an intersectional class analysis and respond appropriately to the fury and frustration of those in the UK right now. We can only hope that it elicits what anger always yearns for: change.

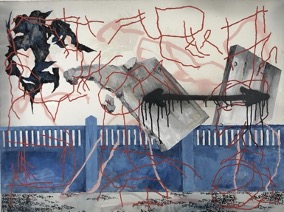

IN CONVERSATION WITH ZOE KRAVVARITI

@kravv_

Interview by Eliza Hart (She/Her)

Zoe Kravvariti is a multidisciplinary artist, who has recently graduated from Glasgow School of Art. In her work she explores the expression of emotion through movement and the body.

TELL US ABOUT YOUR RELATIONSHIP WITH FEMINITY AND FEMALE RAGE IN ART?

For centuries, women have been denied their anger. Whilst silent women have been glorified, angry women have been degenerated. She has been ‘a monster,’ ‘a hysteric’ and now ‘a bitch’. From the moment women are seen as passive, our anger and rage becomes something negative. It becomes a reason to be judged, a reason to stay silent. The opposition between the good silent woman and the bad, angry ‘non-woman’ has been a main focus for my practice this past year. As someone who has felt silenced by anger, I have turned to my work to look for answers. My aim is to depict the burden and experience of ‘femininity’ and suppressed anger. Looking at the representation of women in art, as well as in literature, philosophy and religion, it becomes clear to me how misunderstood and misrepresented angry women have been in the hands of men. Through making, in the broadest sense, many women, including myself, have found a space to speak on their injustice. They have found a space where they can break their silence and reclaim the power.

WHAT DOES YOUR WORK AIM TO REPRESENT?

I have always wanted my work to discuss emotion. We have developed a tendency to keep our feelings to ourselves, as if they are something to be embarrassed of. By expressing and exposing myself in my work, I have experienced personal catharsis. I want my work to evoke emotion, understand it, and most of all respect it. To respect one’s emotions is to respect their nature.

HOW DID WORKING WITHIN THE CONFINES OF YOUR HOME THROUGHOUT ART SCHOOL SHAPE YOUR PRACTICE?

Working within a restricted environment was limiting. However, on reflection, lockdown was surprisingly beneficial for some areas of my practice. I believe that my performance work, where I explore and incorporate improvisational movement, was affected the most by that limitation. Not having enough space led to my improvs feeling controlled. At the same time, it pushed me and I learned to use my restriction as a prompt rather than an obstacle. Currently my home is my studio. This restriction no longer limits the possibilities of a project.

WITHIN YOUR PRACTICE, WHO ARE YOUR BIGGEST ARTISTIC AND NON-ARTISTIC INFLUENCES?

I don’t think there is one specific influence that I can refer to as ‘the biggest.’ I tend to combine multiple references, both theoretical and visual, to feed my ideas. I value both theoretical and visual influences equally. My key influences on my project last year include the book ‘Rage becomes her’, by Soraya Chemaly. This was the starting point of my project and still is a massive influence for my practice in general. Another big influence that inspired my piece ‘Killing the Angel’ was reading Virginia Woolf’s ‘Killing the angel in the house.’ She writes about killing the ‘perfect’ patriarchal woman that exists within her mind, in every woman’s mind. For several years now, Antonia Economou has been a constant inspiration to my practice. She is a dancer and choreographer (and also very dear friend!) based in Athens. Antonia’s work has been a key reference of mine when it comes to improvisational movement and performance. It was through her work I came to love movement.

AS A FORMER GLASGOW SCHOOL OF ART STUDENT, HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT CREATIVE INSTITUTIONS?

Looking back at my experience in a creative institution has left me with mixed feelings, bittersweet I’d say. I strongly believe that the best part of GSA was the people. Being surrounded by so many incredibly talented and unique individuals, I was constantly inspired and its definitely the thing I will miss the most. The fact that for almost two of my university years I wasn’t able to actually use the facilities plays a big part in that bittersweet feeling.

WHY COMMUNICATION DESIGN?

I was intrigued by the word ‘communication.’ Communication can be a poster, an illustration and a photograph, but also a film, a performance piece, a play, a sound piece, a painting and a sculpture. I don’t believe there are any limits as to what communication design is or could be, and I don’t want to have any limits as to where my practice can evolve. I guess that’s why communication design! My practice has always felt multidisciplinary. I tends to rely on a lot of experimentation and work with a combination of media. However, the medium I always seem to go back to, is my body. As I mentioned before, I am interested in communicating different emotions and by using my body as a medium I could translate these emotions into different movement. Through improvisational movement, I aim to create a language that narrates tales that I have struggled to put into words. I use my body to retell the stories that have been told about me, to represent the female body and the burdens of false representation.

WHEN IS YOUR FAVOURITE TIME OF DAY TO CREATE?

I am the most productive and inspired during evening and at night time. However that has led to many all nighters!

WHERE ARE YOUR FAVOURITE PLACES TO VISIT IN GLASGOW?

To be honest, I think the best thing in Glasgow is that there are so many things happening everywhere! The Rum Shack in Southside became a favourite of mine last year, which I discovered by going to GLITCH41. If you are up for a sick gig and a boogie, I would definitely recommend going!

Branded for Your Pleasure

Words: E.B. Artwork: Katie Stewart (They/Them)

As the first of autumn’s leaves drop and all bare skin is hidden under tartan: we fall

unrelentingly into cuffing season. For the chronically single, the season stretching from October to Valentine’s day is but a reminder of a tragic love life. But the warm layers bring some comfort in hiding a worse reminder of your messy breakup, a symbol of your ex-lover permanently embossed in your flesh. The relationship tattoo: a profound gesture of love in an age in which chivalry is dead, its ghost haunted aired DMs; a parading red flag, or a lusty act of desperation fated to be regretted?

All the hottest babes don a relationship tattoo, from Bradford to Beverly Hills. Think Zayn Malik’s tattoo of supermodel-turned-baby-momma Gigi Hadid’s eyes on his lower chest, or, a more recent example, Pete Davidson’s ‘My girl is a lawyer’ stamped across his neck. Better yet, ‘Kim’ burnt and scarred into his chest, branding him part of the Kardashian-Jenner empire along with Skims and Kylie Cosmetics, 818 tequila and Mason Dash Disick Instagram Lives. You could even be like Angelina Jolie and have your lover’s birth coordinates postmarked onto your sleeve; matching celebrity couple tattoos which are so ‘goals’ that they find their way into the drivel of a Refinery29 article.

These often cringeworthy couple tattoos aren’t confined to Hollywood. One of my friends in sixth form fell victim to a similar act of passion. One morning, to our horror, she pointed out a small ‘L’ which had appeared on her ankle like a venereal wart. After 9 months of UTIs and pregnancy scares, he had finally actually given her something that wasn’t going to go away on its own.

Sadly, these tattoos last longer than the relationships in a lot of cases. All aforementioned relationships are now dead in the water; with Zayn and Gigi ending after Malik’s spat with the Hadid matriarch Yolanda; Pete and Kim’s seemingly civil parting, and my friend’s split after her boyfriend pissed their AirBnB bed following 3 beers and a bump. Now, do these little emblems on their body leave them feeling mournful or embarrassed of past flames? Yes. Probably.

Once star-crossed lovers slashed their chests in their desire to spend an eternity together, now they simply get their significant other’s name permanently hot-ironed onto their skin. But are Pete Davidson and Juliet Capulet really all that different? So passionately in love they are but victims of desire and dedication, spectacles for a world to call impulsive and irrational. While it may seem a little strange to the less romantically dedicated, and outright laughable when considering that the relationship lasted but months, is this gesture anything more sinister than a little impulsive? As a young gay man, the desire to brand a fresh and inevitably short fling’s name onto myself to show my undying love for some guy who raw-dogged me on his flatmates Dunelm cushions is a desire I know all too well. Maybe impulsivity is often a reason for this, especially in the case of Pete Davidson, as he and Kim had dated only months before he made the flesh-altering decision. Those in the public eye have an image to upkeep, surely some of these tattoos are nothing more than for the sake of publicity. But what about the more long-term couples? These are less likely to be impulsive decisions, but the underlying reasoning is bound to be similar- it is an act of dedication, a symbol that shows they care enough about their partner to alter their bodies.

So, while in some cases a tattoo may be the permanent result of a lust filled and passionate moment, does this really make them any less a symbol of love? And what does it really matter if they break up? There are always cover-ups and lasers. My friend resolved her ‘L’ittle issue by tacking ‘DR’ onto the end, an acronym for Lana Del Rey. Ironically her symbol of undying love for this chain-smoking boy metamorphosed into one which shows her love for a chain-smoking woman. Better yet, just leave the tattoo as a reminder of your dating history, as tragic as it may have been.

Maybe Zayn Malik’s pecs could one day don a pair of aviators; Pete could add to his hot iron branding to show a newfound love of kimchi, and exclusively date lawyers for the rest of his life. In the dating world, the tattoo doesn’t have to be something that symbolises that you’re here to stay, with easy access to removal solutions. Whether or not you think they’re cringey, concerning, or cute, couple tattoos are here to stay and, for those who cannot afford lasers, quite literally.

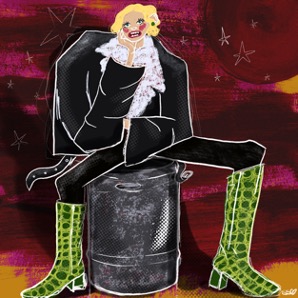

The Lipstick Effect: why we’ll buy a new lippy but not turn the heating on

Words: Kathleen Lodge (She/Her) Artwork: Lizzie Eidson (She/Her)

‘The Lipstick Effect’ refers to the economic phenomenon of an increased desire for ‘appearance enhancing’ products in times of economic recession. We’ll buy a new lipstick,

even when we can’t afford it. While given little airtime outside of flippant cosmopolitan articles, a wealth of evidence places it as good an indicator for recession as employment rates or housing markets. Media narratives discussing recession often feel removed from our everyday lives, littered with unfamiliar jargon, while its effects are all too real. In contrast, the lipstick effect is relatable – for me at least. It’s a refreshing lens, one centering makeup wearers, to look at what we spend on when our spending is squeezed, and why. Disarmingly simplistic, this theory asks multifaceted questions about the relationship between women’s appearance, their finances, and the broader capitalist system.

Straddling psychology and economics, the general preface is that ‘women’ (or, perhaps a better phrase, lipstick wearers) enhance their appearance for two reasons: to attract ‘romantic partners’, and to create a ‘favourable impression in the workplace’, and therefore both of these reasons can somewhat be attributed to the goal of financial security. Lipstick epitomises this ‘appearance enhancing’ element because it creates such an obvious change. Therefore, in times of financial insecurity, this urge increases, and as a result so does the sale of lipstick.

The prior is justified by evolutionary theory: ‘in financial need individuals allocate towards reproduction rather than personal growth’. Rebuffing the frankly offensive assumptions on which this theory relies feels too obvious to give voice to. However, if we distance the act of attracting partners from reproduction and financial security, and instead associate it with casual consenting sex or getting a compliment from a friend or stranger, it’s plausible we would want to provoke such attention in tough times.

The latter gives way to a more complex point. Many of us wear make-up as a part of our routine. It is difficult to distinguish to what extent we do this for ourselves or for others. What is clear though, is taking anywhere from 15 minutes to an hour before work to ‘get ready’ manifests itself as unpaid work. The academic writing on the lipstick effect comments on the gap between appearance and monetary reward, and unsurprisingly fills it with a man. Much of this writing suggests that enhancing one’s appearance to appeal to male colleagues, traditionally those in positions of authority, results in favourable treatment. While it is perhaps naïve to deny this, there are more direct manifestations of this transaction in action.

I work at a pub, and feel the need to ‘put my face on’ for work. A ‘need’ I could attribute to being told at each of my first three jobs that I’d been hired for my looks, that ‘everyone likes a pretty waitress’. Fancying myself as a journalist – more a Carrie Bradshaw than a Laura Kuenssberg – I embarked on my own experiment. Did I make more tips if I wore lipstick to work? The conclusion: they roughly doubled. While far from scientific, it suggested, at least in a job that involves tips, appearance and finances are inextricably linked. It’s a depressing reality, demonstrating how personal decisions about self-presentation become politicised in a sexist society. It makes lipstick ideological.

As the politicians that caused the current cost of living crisis tell us to buy new kettles to save a tenner a year, we’re navigating increasingly stressful daily decisions about how we spend. The lipstick effect documents an increase in spending on morale boosters, and a dampening on spending in other areas. During the Great Depression, ticket sales for the newest Charlie Chaplin film soared. During World War II, ‘morale’ was so closely linked to lipstick that women were encouraged to wear lippy to ‘remind the soldiers what they were fighting for’. Whilst I am aware that I’ve claimed that lipstick is highly political, the purchase of it can also be as simple as a little morale boost – purchasable self-care. Controversial, I know. Whilst the desire to do so may be as a result of capitalist messaging, if it works, women should not be made to feel guilty. Buying, and applying, a new lipstick is a solitary act, but I find it validating that so many of us do it, all at the same time.

We do buy lippy to feel better – even when we’re skint – but the reasons for this are much more nuanced than to attract beneficial male attention. Where academia focuses on the impact that wearing lipstick has on others, I find it’s more about how it makes the wearer feel. It occurred to me during my ‘experiment’ that wearing lipstick is acknowledging that you are being seen – meeting ‘the male gaze’ head on. If it’s worn for the attention it provokes, you are provoking this attention knowingly. The cost of lipstick seems a small price to pay to feel a little sexier, or perhaps to feel more in control, when the world feels so uncertain. If an extra tenner in tips, or a shag, is a by-product, then who’s complaining?

Punks aesthetic legacy: I know what I want and I know how to get it

Words: George Browne (He/Him) Artwork: Joanna Stawnicka (She/Her)

The central realisation behind the counterculture movements of the 1960’s, according to British filmmaker Adam Curtis, was that ‘ if you can’t change the world, in terms of power structure, what you do is change yourself,’ Curtis’s argument is based primarily on the Hippie movement, but it still captures the modern individualism that was also behind the counter to Counter Culture: Punk. A movement centred on the rejection of the institution but one that offered no genuine solutions (anarchy was mooted) meaning individual

self-expression and thus fashion became integral to it. Fashion was the perfect signifier of this individual rebellion: it made this self-change, this rejection of institution, visible.

To define Punk – a term that has become diluted through its appropriation – is a difficult task. To provide it with a definitive definition may even be considered a violence to the term – would this institutionalise it and thus cause its personal and individual meaning to be lost? Regardless, Punk manifests itself as a genre, an attitude, an aesthetic and a cultural movement. In each of these modes rebellion is always the focal point – a visceral rejection of the status quo. A rejection as The Sex Pistol’s ‘Anarchy in the UK’ reveals in the lines ‘I don’t know what I want/ But I know how to get it’ – not in favour of any alternative. Punk’s main aim, therefore, was to establish a radical voice: one that showed no concern for the established modes of discourse and was able to convey the anger felt by the young. Punk’s individualism and fury stemmed from the combination of post-war collectivism and the entrenched establishment that was causing Britain’s economic and political systems to fail and its social situation to deteriorate. The idealism of counterculture had collapsed. Punk was born in an era of ideological failure and poverty – all that was left was the personal. As Sheila Rock, a photographer whose photos have become the iconic images of the iconoclastic movement, says Punk was about: ‘everyone…doing their own thing’.

But what exactly did doing their own thing consist of? Vivienne Westwood stated that she became bored of the movement’s tendency to merely ‘spit’ and ‘bash their head against institution’. It was Westwood and her partner Malcolm Mclaren (who also managed the Sex Pistols) and their shop originally known as Sex (1974-1976) and later renamed Seditionaries (1976-1980) on Kings Road, in London, that provided the foundation and direction of Punk style. It was here that Westwood enacted the most insightful modes of fashion rebellion within the Punk movement. If Punk music was about rejecting the institution through short, shocking and antagonistic screams of rage, Westwood’s clothing was about attacking the beliefs that accommodated the institution. Her clothing angrily dismantled the idea of taboo, the sexual suppression mostly manifested in time through the treatment of women and gay men: nudity was made public. Images of homosexuality were made explicit. Bondage was deconstructed to be made ‘romantic’. Westwood knew that the liberation of the individual that Punk sought could not occur if the body, in particular the female body, remained a clandestine suppressed entity.

Westwood’s aesthetic choices during the period of Sex and Seditionaries contain a thread of what the current Pre-Loved and Vintage movements are based on: a desire to look to the past and/or the ignored in order to create a better future. Her work can be distinguished from Punk through its wider ambition and intellect: she sought to show how youth rebellion could offer some form of permanent liberation. Yet while her desire for sustainable rebellion arguably remains in her brand’s current emphasis on ‘Culture not Consumption’, her clothing is now inaccessible for many – her trademark necklace has become a symbol of wealth as opposed to emotional and political beliefs. A complete loss of the initial invigorating anger of Punk is acutely evident. The fascist regime absorbed it all and marched on. The safety pin has just become another accessory.

With the current political and economic state of Britain holding strong parallels with that of the era of Punk it is interesting to consider whether there is any ideology that can usefully be retrieved from the movement? The original incarnation of punk was so wonderful – so

creative, visual, innovative and challenging that it is easy to forget that it was once just another youth culture. Like all youth cultures, it has had an undeniable impact, but only on culture: our economic and political systems remain unperturbed. With an impending environmental crisis, we must understand that no fashion aesthetic will save us. One of Punk’s consequences is consumerist individualism – we now know what we want and we know how to get it. Thus we realise that a return to collectivism is necessary – individualism and fashion cannot be part of the movement that is now required. And perhaps this is rejection of the very ethos of the Punk movement itself. We must see red together.

The Infuriating Cost of Entry to the Boys’ Club

Words: Sytske Lub (She/Her) Artwork: Ruby O’Hare (She/Her)

It was the third year of my medical degree. I was in an operating theatre retracting the wall of a femoral artery, having convinced the surgeons to let me scrub in. The surgery was going well. I was locked in conversation with the consultant surgeon about the toils of medical school, and I was about to roll the discussion onto one particularly irksome construct: the fabled Boys’ Club.

Oh the frustration, I cried, to throw so much effort into exams, coursework, and placements, only to watch your success get trampled by some boy. Connections in the field pave a convenient path to the most exclusive of projects and the deepest of networks. The members – exclusively male – are groomed to be the best of the best, and outsiders don’t stand a chance of catching up to them.

‘I find’, explained the consultant in that trademark clinical confidence, ‘That having a Boys’ Club is actually rather useful.’ He went on to highlight the benefits of sourcing motivated, experienced individuals that had been vetted by his esteemed colleagues.

Did I just hear that right? Did he realise that he was essentially telling me, to my face, that between someone like me (motivated, high-achieving, but broadly directionless at such an early stage in my career) and someone who had been passed between the top dogs in the Boys’ Club, he’d appoint the latter in a heartbeat? Steam bellowed from my ears like an old stovetop kettle. My fists clenched with rage, I looked up into the surgical lights and screamed in disgust: “Did you not just hear what I said?” Except, of course, I didn’t.

The Problem

The definition of a Boys’ Club is “a male-dominated organisation, especially in business, that excludes or mistreats women”. Most studies refer quoted here refer only to ‘women’, but it is generally accepted that the culture excludes the majority of female-identifying and non-binary individuals.

The concept is well known across the science and technology industries. In medicine, surgery especially, the encapsulated core of the senior workforce is overwhelmingly male. The percentage of women in consultant roles, though slowly climbing, is only 36% across medicine as a whole. This is despite more women than men entering medical school since 1996-97, with 64% of acceptances awarded to women in 20204.

In the surgical field, the divide is greater. The biggest disparity is seen in trauma and orthopaedics, neurosurgery, and cardiothoracic surgery, where women comprise less than 10% of top posts. Even when accounting for surgeon availability and expertise, male doctors in surgery are also disproportionately more likely to refer to other males.

The excuse often given is that women desire a more family-friendly lifestyle, and there simply aren’t enough finishing intensive surgical training as a result. This may be true for some of course, but the reasons for many are far more complicated.

While beneficial in the ways outlined by that surgeon, the Boys’ Club seems very much to be a closed circle. You may get near enough to sample some of the benefits, you may even outperform members of this exclusive group, but the most senior positions are kept under lock and key.

Beyond the Operating Theatre

The issues of the Boys’ Club stretch further than just clinical medicine. A 2018 report for the the British Medical Association7 revealed a culture of sexism and discrimination across its staff, and a 2014 review in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine revealed women are consistently underrepresented in most branches of academic medicine8.

The problem can be seen as early as medical school. Around the table of a society dinner last year, the evidence was particularly damning. The organising committee’s gender split weighed heavily against the males, but looking around at every speaker, faculty member, and workshop-leader, there was only one female at the table. And it’s not as if there weren’t any options – they simply weren’t invited.

The Future

In medicine, the numbers of female-identifying students managing to climb to the top rung of the ladder is slowly increasing. But the exclusive culture of the Boys Club will persist, likely, for some time.

And yes, I am angry. You walk the same path just as well as everyone else for your entire schooling, and suddenly you find the path has diverged. You commit yourself to the long, uncertain corridor called medical school only to reach a doorway and not be able to walk through it.

How do you get around this invisible wall? How can we actually break it, seeing as the bricks are laid down from the earliest point of a medical career? The answer is still unclear.

Boys’ Club entry fee: free to immediate family members, a word of approval for associated males, and incalculable for the rest of us.

Behind Red Zones

Words: Amelia Coutts Artwork: Magdalena Kosut

You do not have to be a scientist to see for yourself how air pollution has increased in industrial cities. In 2015, large smog clouds were visible in London, and the effects of air pollution are responsible for around 7 million premature deaths globally. To make life a little easier, air quality is generally measured using a colour-coded point system, red indicating dangerous levels. Areas of low air quality are red zones.

Countries with large amounts of red zones include India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, with over half of the top 20 most polluted cities being in India. A boost in industrial growth in South Asia has led to increased air pollution and the popular farming practice of stubble burning, which produces pollutant-filled smoke clouds visible from space, is likely also to blame. Unfortunately, in India, this has disproportionately affected young children as they are more vulnerable to developing health complications and are unable to avoid exposure.

But this situation hits closer to home, too. In boroughs in London, levels of pollution are also significantly high. In the recent art piece Breathe: 2022, inspired by the death of Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah whose asthma attack was made fatal by the high levels of air pollution, scientist and artist Dryden Goodwin brought attention to how BAME groups and lower-income individuals in London are disproportionately affected by polluted air. Unless you find yourself in the lux mansions of upmarket London, it’s likely you’re breathing dirty air. Studies supported by the British Lung Foundation revealed that residents in more deprived London boroughs are up to two times as likely to die from lung diseases than those living in Kensington or Chelsea, some of London’s wealthiest areas.

Similarly, near the Mississippi River in the US state of Louisiana, majority-black communities live alongside a petrochemical corridor, which has grown across former plantations. Toxic waste produced by industrial sites has regularly spewed into the air of neighbouring communities with little repercussion, an effect described as ‘environmental racism’. The area, as a result, has become known as ‘Death Alley’, where rates of cancer amongst residents are high. In these red zones, marginalised residents are largely powerless to prevent the continued disposal of waste.

Comparatively, the much smaller island of Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean has actively worked to reduce the damaging legacy of chemical manufacturing sites that have been responsible for one of the highest rates of air pollution associated deaths in the Americas. The country has committed to reducing short-lived climate pollutants and currently has air quality listed as ‘Good’, putting it well out of the red zone. This is a stark comparison to previous examples, despite having a GDP per capita that is roughly only two-thirds of the UK’s. Such David v Goliath action makes you question why we could not do the same.

Several factors have contributed to the air quality in many of these red zone areas. However, like in the case of Death Alley, Louisiana, those who face the greatest health consequences are the lowest contributors to pollution. Outsourcing of manufacturing and resources by the Global North could be to blame for the exacerbation of pollution, like the rapid growth in demand for fast fashion and its impact on textile mills and clothes manufacturing in India. Similarly, in Trinidad, natural resource export to the US created the demand for industrial sites that resulted in the need for clean-up programmes, although thankfully these were largely successful. Thinking critically about the main contributors to air pollution and, subsequently, global warming may lead us to break down misconceptions surrounding the role lower-income countries and emerging economies play. Is it fair to criticise Pakistan or India if our own government cannot maintain safe air?

That is not to say red zones will become a norm. In Glasgow alone, like in many other cities across the globe, governments and councils implement strategies to reduce emissions and keep the air clean. Low emission zones, in effect now and within the next few years, electric buses and the encouragement of cycling as a preferred mode of transport show that change is happening. Even education is an important tool in ensuring the future can look greener in person and on air quality charts. Public exhibitions and data available could indicate that education on such topics is becoming more widespread and accessible, ensuring we do not find ourselves making victims of toxic air pollution responsible for actions outside of their control. Hopefully, with this and the efforts made by those in power to make the right decisions, we may find we won’t be seeing red much longer.

Little Red

Words: Kitty Rose (She/Her) Artwork: Katie Stewart (They/Them)

Little Red lives in her little house in her little neighbourhood in a little forest. In summer, there are strawberries to pick and wildflowers that grow, and in spring the birds chuckle every morning with sweet song. Autumn brings the leaves down off their branches, in a flutter of red and ochre, and in the darkness of winter, Little Red’s windows are lit brightly as the snow falls gently outside. Her red coat, gloves and scarf hang by the door on a singular hook, where the letters posted through the letterbox are addressed to her, and her only.

Little Red lives her little life; she does her daily tasks as the hours go by. She hangs up her washing to let it dry in the wind, and lays out a place for one at the table – the knife, fork and spoon are friendly companions to the china plate that sits atop the tablecloth. Every morning, every afternoon and every evening is the same. There is a perfect symmetry to this solitude – why should she complain? It’s reliable, stable, solid. A fairytale. A postcard. She is safe because she can never be disappointed. No one can let her down or upset her. She only has to look after herself in this house, where dust collects on the mantelpiece, and the sun rises and sets. In her little house, in the little forest, Little Red is safe. But she wishes she had the blur of shape and movement inside the walls, conversation and laughter to fill the rooms, and for cushions and chairs to mould to the shape of a human body other than her own.

Little Red is lonely, and she’s afraid. Because this loneliness is beginning to scare her. It is a small child that she nurses like a mother, curled up in the pit of her stomach, in the concave of her belly. It is a monster that rears its head, wild, yellow eyes aglow and breath hot and rancid. It is a pulsating heartbeat that runs an internal clockwork of cogs and wheels where if it stopped, she would stop too, leaving a broken doll. She aches for danger, for terror, for heartbreak, for all the things she reads about in her storybooks, just to feel something else. Rotting in her own skin, in her shame, in her own house, in a skeletal state of what life could be.

One night, in search of a friend, she puts on her red coat, gloves and scarf, lacing her boots up with her pale hands. A storm blew leaves spotted with a blackened decay in a circle round her small feet, as she rehearses what she would say to someone – something, anything.

A figure of red and white, alone, in the dark and scary forest that doesn’t feel like home anymore.

She goes up to trees, to the foliage, looks up at the stars and the moon and asks them to be her friends, but they turn away. She is too ugly for them, too earnest, not interesting enough. Her inadequacy, her averageness to them all, is a brand on her forehead, a stamped red wax seal on her lips.

A dark figure, brusque and prickling. A gesture. It doesn’t matter who he is, because she feels noticed, she feels seen.

A big, bad, wolf.

In the belly of the big, bad wolf, Little Red smiles. It’s silly, she knows, but it is nice to feel something different. She has prayed, with hands clasped and knuckles white, to feel something different for so long. At least she was brave, for the first time in her life. For she was always a coward, a little frightened, so desperate to feel loved. And so now she sits,

In the belly of the big, bad, wolf.

A Scarlet Letter, and Controlled Substances

Words: Paul Friedrich (He/They) Artwork: Magdalena Kosut

I yawn—a

Her poppy-coloured dress clings to her torso as she cycles paast.

‘Mehr schlafen!’- ‘sleep more’,

her lungs wheeze, she cackles and is followed by an air

of forty years of menthol superslims.

I spent the night turning in my bed like some kind of boudoir kebab skewer

because I was on speed (prescribed)

I spent the morning folding laundry, then I watched the dust

settle on my sheets in the Evening (!) sun

What happened?

There was a pitch that needed writing, so I took another pill.

They’re oblong, white—

when I take one in my hand

like a tiny rain-stick something shifts inside,

I wonder, when I swallow them, do those grains stain red?

Absorbing by what marked me before, invisible to some;

but when you listen closely, lift me up and shake me, can you hear them shift?

If I had just tried harder, pulled myself together,

If listening to someone speak was not so exhausting;

If I’d not been so stupid, lazy, worthless—

Would I have published novels,

if I had just stopped scrolling?

The other kids can do it-

sin(x)/x as x approaches 0

She said

“if you did not talk so much you might know that it’s one.”

There are sixty unread messages but the toaster-crumbs need cleaning.

From the centre of my fishbowl I see – barely:

raised hands, obscuring lips

furtive eyebrows raised, side eye given

‘Too much, too loudly, too strong, too rude?’

The rush folds in my ears and stings my eyes and

pricks my skin and fills my vessels and

scarlet rushes in my lungs as anger, violence, and blood.

But on some days it is passionate, and warm, or hot

when it burns fuel in my chest;

two decades it was here like a stowaway and thief.

But I am this engine which is me, a cyborg.

If I had only not…

who can tell what would be?

Two decades later there are letters I can put to it, excuses for the stains

But the fire cannot read; it burns, gives life, unchanged.

If I had only not…

I could not speak

with hot titanium buried in my flesh.

GLASGOW UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE

SEEING RED AUTUMN ‘22

CONTRIBUTORS

Words:

Soumia Serhani, Isobel Dyson, Kate McMahon, Luisa Hahn, Robert Goodall, Alex Agar, Ellen Ode, E.B., Kathleen Lodge, George Browne, Sytske Lub, Amelia Coutts, Kitty Rose, Paul Friedrich

Artwork:

Leotie Whitelaw, Lewis Aitken, Louis Managh, Ben Woodcock, Sophie Aicken, Katie Smith, Lizzie Eidson, Ruby O’Hare, Katie Stewart

TEAM

Editors-in-Chief: Ava Ahmann & Conal McGregor

Editorial Director: Esther Weisselberg

Features Editor: Izzie Chowdhury

Culture Editors: Nina Halper & Dylan Richards

Politics Editor: Jeevan Farthing

Style & Beauty Editor: Mia Squire

Science & Tech Editor: Rothery Sullivan

Creative Writing Editor: Violet Maxwell

Copy Editors: Marcus Hyka and Hannah Parkinson

Visuals Director: Rory McMillan

Photographer: Louis Syed-Anderson\

Graphic Designer: Nancy Heley

Communications Designer: Josh Hale

Art + Photography Curator: Eliza Hart

Editorial Artists: Magdalena Kosut, Joanna Stawnicka, Sophie Aicken, Lewis Aitken, Lizzie Eidson, Katie Stewart, Louis Managh

Website Designer: Mary Martin

Digital Media Director: Eve Dickson

Social Media Managers: Leah Sinforiani and Sophie Wollen

Events Manager: Charlotte Macchi Watts

Advertisements Coordinator: Jenn Yang

Front and back cover designed by Eliza Hart

GUM JOURNAL 01 – OCTOBER 2021

Smaller, Weirder, Louder

Contents

Features

The Good Immigrant – Mayuri Gadi

Politics

Neighbourhood Watch: Exploring the Roots of Kenmure Street Protest

– Conal McGregor

Culture

Time to Come Out: On Temporalities and Queerness – Lucy Danoghue

Sex, No City

Your First Month in Rural Island – Lola O’Brien Dele

A Guide to Radical Crafting

Life in Plastic, It’s Fantastic – Izzy Chowdhury

Sci+Tech

Finding Solace in SEGA – Cameron Rhodes

Style+Beauty

A Case for the Universal Appeal of Anime Fashion – Meriel Dhanowa

Creative Writing

Stain in the Sea – Meli Vasiloudes Bayada

Features |The Good Immigrant

Mayuri Gadi (she/her)

When introduced to any mass of information, human beings often make sense of it by simply categorising it into good or bad. We also do this when analysing others and deciding their significance in our lives. This categorical thinking is misused when people who hold themselves superior attempt to organise immigrants into ‘good’ and ‘bad’. This attitude is driven by the undying systematic racism we witness in the UK. A ‘good immigrant’ is deemed as one who ‘gives back’ to the Western economy as it is believed to be their duty for being allowed to immigrate in the first place. This capitalist sentiment perpetuates the belief that if an immigrant is not fulfilling this responsibility, their move is not justified. However, what many fail to recognise is that conforming to this ‘good immigrant’ title can lead to the sacrifice of their cultural identity as they must adapt to Western civilisation to avoid seeming abnormal or unknown, and therefore a potential threat.

This mindset of classifying immigrants has continued for decades, despite recent social advancements. It not only promotes Western dominance, but also a confusion of identity for many immigrants. In Nikesh Sukla’s The Good Immigrant, comedian Nish Kumar talks about his experience of growing up in the UK and constantly being mistaken for almost every ethnicity other than his own. This has a bitter effect on immigrants as it results in a personal struggle between being unable to call the country you are living in home, whilst not being able to identify with your homeland and cultural values. As a second-generation immigrant I have witnessed first-hand how this has impacted my parents struggle to form any true cultural identity.

The term ‘BAME’ highlights the unfortunate reality of individual cultures not being recognised, as everyone who is not white is jumbled into one. For example, the “A” meaning Asian assumes all Asians fit under one category. I personally find this absurd because there is such a variety of people just within India, so how could one term ever encompass an entire continent? This ignorance makes me wonder why the West is so glorified and able to escape any stereotypes, while the East is bound to many.

It is a common assumption, especially in India, that when one moves to the West it is a sign of intelligence or accomplishment. Anytime I go back to India, I often hear friends or relatives assume that because I live in England, I am living a higher quality of life. This is true in many ways, such as increased human rights, and I am beyond lucky for the opportunities I face. Many countries in the Global South are dealing with issues such as serious poverty and a lack of women’s rights. However, the social issues faced in the UK should not be ignored simply because they are less pressing. Just this month, my social media feed has been flooded with information regarding the government encouraging laws against protesting, plans to cut universal credit, and refugees searching for this ‘better life’ being sent to animalistic detention centres. Alongside these unacceptable headlines, the incessant neglection of Western terrorism further highlights the power and status the West holds.

Despite any social progression, we’re still being programmed to have a set view of the countries within the Global South as being irrational and consisting of a chaotic culture. In contrast, the Global North is seen as logical and its countries are considered, according to Jan Heller, ‘products of modern thinking’. This inaccurate understanding of the East-West dichotomy is hugely a result of the UK’s unreliable school system. School history syllabuses tend to concentrate on the Tudors and World Wars, at the expense of more consequential events such as British Colonisation. Furthermore, there is no mention of the long-lasting effects the Empire had on ethnic communities which continue to prohibit their growth. This information taught all over the UK fuels the mindset that immigrants are not fit for living in the West unless they prove themselves by ‘giving back’ in some capacity and therefore attaining the title of being a ‘good immigrant’ as opposed to a ‘bad immigrant’ – one who reflects their culture, but risks being stereotyped as uneducated.