We are living on the threshold of so many transformations: witnessing the beginning of the Anthropocene, anticipating the loss of most of our wild animals by 2020, going through a cycle of technology-induced mass unemployment not witnessed since the Industrial Revolution. Yet in this whirlwind of changes, there are still people sticking their fingers in their ears and pretending none of this is happening. As consumers, many of us feel a frantic need to do something, anything, that counts as a positive contribution. To answer this need, it has become increasingly important for companies to display an image of social responsibility. We are just as driven by our consumerist desires as before, but it has become more commonplace to silence the twinges of guilt with bright labels promising Fair Trade, Local and Organic, A Better Tomorrow. But is ‘harm-free’ a real option or a comfortable self-delusion? According to a new report, the coffee industry could be the poster child for this dilemma – and, because of the hardships it is going through, a harbinger for a less pleasant tomorrow.

In October, Finnwatch, a Finnish NGO focused on global corporate responsibility published a report on social responsibility in the coffee industry. The report revealed that despite pretty Fair Trade labels and socially responsible brand image, the companies dominating the coffee market were linked with human rights abuses such as employing child labour and exploitative working conditions in the producing countries. The report was a slap in the face for many Finns, the biggest coffee consumers in the world. An in-depth examination of the British coffee industry, or any other industry producing everyday goods, would most likely reveal similar harsh truths; across all business, money talks more than any `humane´ considerations.

In Britain, coffee remains the less popular hot drink— the average person consumes just below 3 kilograms a year, a quarter of Finnish coffee consumption. This still translates to over 70 million cups of coffee every day, however. The coffee culture here is stronger than it used to be, but for many people, the quality of coffee is not something worth mulling over too much in the supermarket aisles. The taste for expensive speciality coffees in fancy cafés seems to be increasing, but the general attitude is reflected in the fact that almost 80% of the coffee British people buy for their households is instant (in Italy, sales of instant coffee make up one percent of the market). For many British people, coffee is a cheap everyday necessity, murky crumbs spooned from a jar; an afterthought compared to the highly ritualized gloss of afternoon tea.

However, in the not-so-distant future, this might be changing for coffee drinkers across the world, whether they prefer to purchase their beans ground to dust and freeze-dried or fresh and unroasted. Coffee might be on its way to becoming a luxury item, whether we want that or not; unfavourable weather conditions caused by climate change have been hindering coffee production across the globe. Many of the workers in coffee-producing countries suffer from aforementioned issues of harsh working conditions and unfairly low wages. Combined with the reduced yield from their crops, the scenario suggests dark clouds on the horizon for many of those earning their living from coffee – not to mention the millions of people employed in coffee-related industries in the importing countries.

As coffee becomes more scarce, its producers should be entitled to more respect – and fairer wages – for their hard work. It is interesting how these two obstacles the coffee industry is facing could be intertwined. The scarcity of the coffee plant could lead to prices going up globally, and thus coffee becoming a more valuable export commodity, the luxury item it was once considered — or it could mean even worse times for coffee growers, with international companies further trampling the producers’ rights to maintain affordable prices in the supermarket. As for myself, I would be happy to consider my coffee a luxury and pay a higher price, if I knew it meant something for the producers somewhere far away. The problem is that even with the labels on the packaging promising social and environmental responsibility, it remains complicated to find out what goes on in the early stages of the production chain. To fulfil the promises of social responsibility, companies need to step up their transparency game. Many of them won’t, effectively confirming that it’s all just a pretty illusion.

Text by Kaisa Saarinen

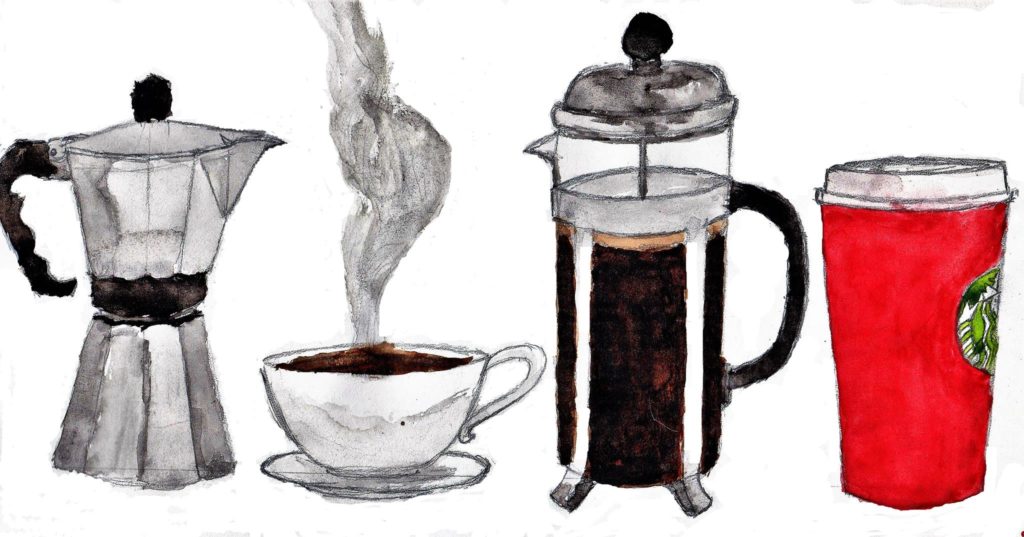

Illustration by Clare Patterson