Words: Eva Lopez-Lopez (she/her)

Artwork: Rory McMillan (he/him)

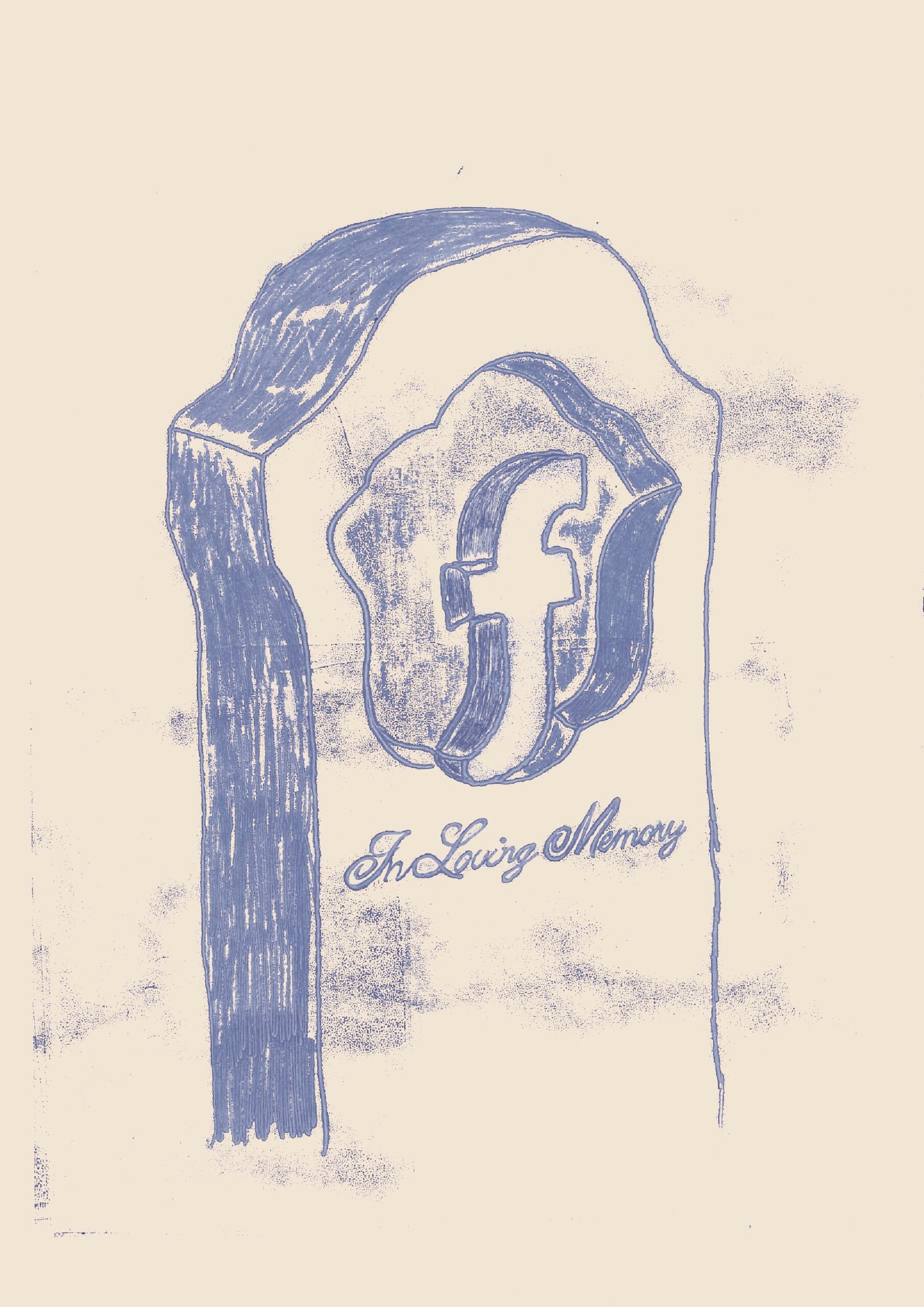

This article features in our third print issue of the year, Ashes to Ashes.

Facebook recently reminded me that it was the birthday of a loved one who had recently passed away. It was a cruel joke, in its own right: no one thinks about what to do with the accounts of the deceased. Put them on private? Delete them like they never existed? Leave it as it is? Unfriend them? Facebook does not care; Facebook does not know. The notification will show up on your phone without mercy.

I had a conversation a few years ago with a family member that told me how morbid he thought social media was making memorialisation. It is obviously painful losing someone you love and we already put our whole lives on Facebook, so why would our deaths be different? It is not unusual to publish a post trying to put in a paragraph or two how much this person meant to you, how much you’re going to miss them, and how heart-wrenching it is to imagine a world in which you are facing it all without this person, now gone. And your friends, family, and co-workers (and people who you have added as “friends” because you shared a seminar in first-year of university or because they sold you a sofa once) will scroll down their timeline, read some of your most personal and intimate words and see a few pictures, a few memories that you cherished and wanted to capture and share. They might press “like” (do you really like this?) or even a “heart”, and, if they can spare a few seconds, they might even comment ‘I’m very sorry for your loss’. The worst part is that it probably is genuine, but it feels pretend and disillusioned. You are alone in your house, with your phone in your hands and no comment will change that.

Remembrance sites and posts about loss make me feel very emotional, but at the same time totally detached from the concept of death. It’s difficult to express the immanence of existing and suddenly leaving an absence, because you cannot ever leave the Internet; on the Internet you live forever. Online, there are so many profiles, and so much information, that it won’t be as obvious that you’re gone. There’s not an empty seat at the dinner table. Business as usual; people are scrolling again.

At some point, around 2100, we will probably all be inactive profiles on Facebook. It could be because we abandoned it in 2050 for another better social media (is it even possible to create a good one?), because we got tired of always being online, or simply because we died. It is eerie to imagine billions of Facebook profiles vacant, inactive, belonging to dead people who will never post again. Some type of digital liminal space. And let us not forget the waste that comes from this. We seem to forget that the Internet is not an immaterial project that translates from our laptops to “the web”. Our data is stored and powered by giant computers and servers that occupy kilometres and kilometres of territory. They are powered through depleting the energetic resources that are already limited. Our profiles will be caskets not only of our online personas, but also of the Earth.

However, I do have to say that I find some comfort in graveyards, even digital ones. Somewhere, someone may come across your name and know who you are or maybe just know that you’re a stranger who wrote something funny, or meaningful, or stupid, or weird, or incredibly frustrating. They will know you were there, and you existed. That you had a life, just like them in the future. We all want to be remembered forever, right?