[Written by Natasza Biernacka (she/her)]

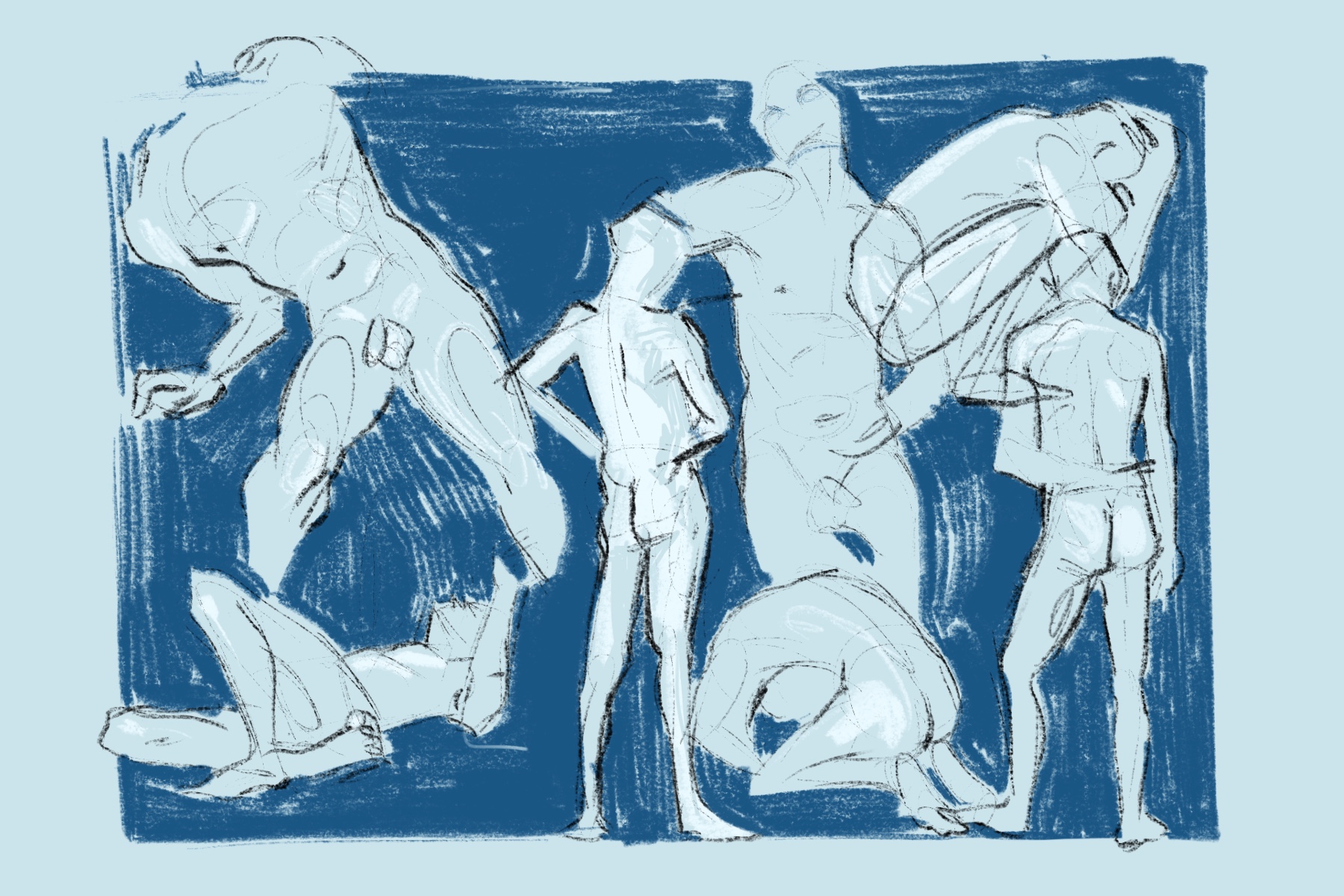

[Art by Yana Dzhakupova (she/her)]

We are not used to calling men beautiful. Our society is more comfortable with the idea of handsomeness as the “gender appropriate” compliment for men. Historically, the way that masculinity and femininity were socially constructed has gendered the word ‘beautiful’. The treatment of women as objects of beauty and desire has been successfully normalised, with vulnerability and fragility being made innate to the concept of beauty. As a result, the conversation about the daily, overwhelming pressures that these beauty standards have created revolves predominantly around women, despite the fact that men likewise battle with their own set of unattainable standards.

Being beautiful carries more expectations than handsomeness and it is a broader concept than being attractive, taking more characteristics into consideration. Giving pleasure to the mind and the senses is one of the obligations women are expected to embody to be considered truly ‘beautiful’. Because giving is not viewed as inherently ‘manly’, handsomeness is not dependent on internal characteristics. In contrast, the functional definition of being handsome focuses on the externa; one’s attractiveness and typically idealised masculine attributes, as defined by the media and pop-culture. When it comes to fashion rules, it is widely accepted that men wear clothing that allows them to conform to these expectations. Therefore, we are not used to seeing men in dresses, skirts, or silk, because the current boundaries of fashion, as set by social norms and reinforced by mainstream culture. Pak Fun Chiu underlines this in his article for Hajinksy, Untying The Bounds of Menswear, where fabrics are a way of teaching us the acceptable norms of gender in relation to fashion.

Popularised in the mid-20th century, we have internalised the sight of a woman wearing an oversized padded suit, as a symbol of male power, strength, and perseverance. This realisation feels familiar, it offers a sense of comfort. More than that, it has become one of the most praised fashion trends on social media and in fashion magazines, with publications such as HommeGirls, focusing exclusively on dressing women in men’s clothing. Despite the troubling idea that masculine dress is still used to connote power, the same flexibility in clothing and textiles has yet to be offered to men. We praise the adoption of the masculine form for women and rarely do the opposite, but how is this stylistic choice more aesthetic than a man in a dress? This is an example of how the society we live in is still not ready to allow men to express their identity through a wide range of emotions, feelings, and fabrics. It is a continuation of our default acceptance of the superiority of stereotypically ‘male’ characteristics like strength and power, reinforcing misogynistic ideals. Vulnerability, sensibility and being open about one’s emotions are still viewed as a sign of weaknesses, and taboo for men to engage with.

What protects us from these unattainable standards of beauty, is employing vulnerability and openness. It is precisely what we need, with body positivity movements on social media fighting to democratise our standards of beauty, to make them as inclusive as possible. However, the taboos regarding male beauty make it hard to address the unrealistic standards of male appearance being promoted on social media, which are mainly the courtesy of fashion brands. It is essential to consider the effect this has on our everyday lives. We are still not used to men being open about their feelings or expressive about their emotions. Therefore, the debate on liberating the male appearance remains extremely challenging, as mainstream culture is designed to stifle any attempt at breaking down these barriers.

We live in a culture that values appearance above everything else. Social media makes us conscious of how we look every second of our lives, which is not in favour of anyone’s self-esteem. Men’s preoccupation with handsomeness becomes especially dangerous when we consider the effect it can have on their wellbeing and mental health. There is no depth nor greater meaning to handsomeness, and it is also no place for vulnerability and fragility. In an attempt to save beauty’s shallowness, we invented the complement of being ‘beautiful on the inside’, as a type of society-wide coping mechanism. Women are told they can possess inner beauty and that it is beautiful to open up about the hardships that they are going through, while men are taught to keep everything inside. This is perhaps the most harmful effect of depriving men of the notion of being beautiful.

I believe that we should get into the habit of calling men beautiful in order to undo the effect of what the oppressive cultivation of toxic masculinity has done to masculinity itself. Without calling men beautiful, we cannot fully combat our narrow and exclusive understanding of beauty, despite all our best efforts.

References:

Jelisaveta K. Milojevic, Beauty as a Gendered Word (University of Belgrade, 2018).

Pak Lun Chiu, Untying The Boundaries of Menswear (Hajinksy Magazine)