Words and Artwork: Tess Hardy (she/her)

Cue: Let the Light In by Lana Del Rey

The artistic canon is historically masculine-dominated. No question. Ernst Gombrich, the “godfather of art history” wrote The Story of Art without mentioning one woman. Women, both in art and society, are so often reduced to geniuses cursed by their gender like Tracey Emin, Frida Kahlo or Artemisia Gentileschi, or silent muses like Lydia Délectorskaya the muse of Henri Matisse; traditional archetypes of virgin mothers, doting wives and Madonna whores. As a subject matter, women so often exist in the domestic sphere enchained by the patriarchy and have gone unseen and unheard for centuries. Yet, amidst the biblical, masculine-dominated storm of the 17th Century Renaissance, one painter from the city of Delft in the Netherlands emerges from the clouds, quietly diverging from this homogenized world in almost every way possible.

Enter, Johannes Vermeer.

Vermeer is one of the most venerated Dutch artists of all time; a national icon of the Netherlands. Yet his image is a rather mystical, enigmatic one. Countless galleries are inundated with Rembrandts’ and Rubens’ but only 35 Vermeer’s exist. Alone, there are more of Rembrandt’s self-portraits than entire oeuvre of Vermeer. He is only seen once in his work: turning his back to the viewer, remaining anonymous. Left in his wake there are no letters or diaries, no students or masters, merely his children and his paintings.

A trademark “Vermeer” consists of a small canvas that is transformed into a window, exquisite shading, blue dresses, deep folds of fabric, immense detail and young women (his subject of choice) simply existing. Everything in the painting feels precious and is visually articulated with acute precision and craftsmanship. Traditionally, 17th century artworks were obscenely grand pictures that towered imposingly over the viewer. Embellished with extravagant demonstrations of wealth or religious devotion.

Vermeer, on the other hand, was a master of the intimate. His works became mini worlds, absorbing and relishing in a singular moment. His glorious vision invites the viewer in to witness his masterful elevation of the ordinary to the marvelous. Our presence with these women, oblivious of being observed, feels like a privilege. We encounter them indulged in their solitude, absorbed in their occupations, in A Room of [their] own.

Vermeer fused together various methods to create his own style. He steered clear of harsh lines, opting instead to bathe his figures in light and shadow. Da Vinci said black served only for shadows but Vermeer uses colour in his shadows. Take that Da Vinci. A particular pigment called “Green Earth”, used near the eye and in the base of the flesh tones. Vermeer is the first and only painter to do this.

It is heavily theorised that Vermeer gained his astute understanding of shadows through embracing emerging technology: the camera obscura. Back in his neighbourhood in Delft, the Catholics next door helped Protestant-raised Vermeer let in the light through the technological gift. Literally. Vermeer used this device to observe the world around him, seeing light and shadows from new perspectives. This aided him in pioneering never-before-seen artistic expression.

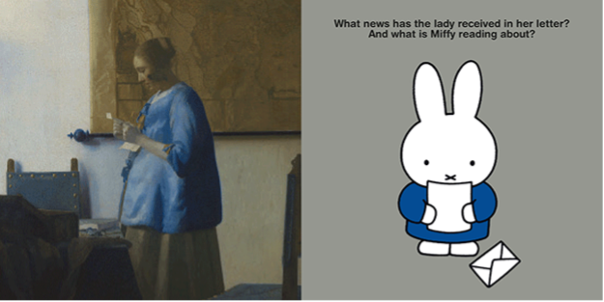

While writing this, I looked over to my left and saw a little rabbit looking at me, sporting a dress of the Vermeer blue we have come to know and love.

Enter, Miffy.

Miffy, like Vermeer, was ‘born’ in the Netherlands in 1955 by the graphic designer Dick Bruna. Bruna fused stories he told his children with geometric paper-cutting techniques of Matisse and Mondrian. The result of which is a newfound expressive minimalism known as “Nijite” in Dutch, or “Miffy” in English.

Like Vermeer, there is very little information available on Bruna. They are both understated-genius figures, resistant to capitalist demands and mainstream media. They do what they love. Despite the simplicity of Miffy’s design (two dots and cross for her eyes and mouth) Bruna conveys the slightest change in emotion. His work is so evocative of the subtlety of emotion, like Vermeer, it appears magic. Both have made their career through stripping characters down to their very essence.

On the surface, Vermeer and Bruna exist at polar opposite ends of the artistic spectrum and the age range target. One a “high art” grand master and the other a childhood storybook graphic designer, yet they share time-defying connections.

Both were captivated by small, intimate stories, focusing on a single activity, often taking place in a domestic environment. They share a fondness for the colour blue, such a particular shade that even while writing this the very tone and hue springs into mind.

The connection I love the most between Vermeer and Bruna is the expression of girlhood.

These girls are left to simply exist. On the page, in the canvas, in the corner of the room. No nudity, no abuse and no sexualisation. They carry out their activities without performance, without regard to an audience.

I must admit to you now, I am filled with a sense of sadness even having to express delight at a young woman being shown in such a simple way, but I know these girls. I know how it feels to sit, get dressed and put on my jewellery piece by piece or go to a gallery and revel in such a childhood feeling of joy often disparaged by society, shown by Miffy through the two dots and cross of her face.

Both Vermeer and Bruna through their lives and artistic careers, fused new concepts and techniques in each of their retrospective works. But the messages intertwined in their work becomes even more potent when examined together. They are artistic soulmates, defying time and mortality. They live on through their work and acknowledge the experience of girlhood so often forgotten, but not by them and not by me.

Closer To Vermeer, 2023, Suzanne Raes

The Story of Art, 1950, Ernst Gombrich

A Room of One’s Own, 1929, Virginia Woolf

Uncovering the Jesuit influence on Vermeer, one of the Netherlands’ greatest painters, 2021, Christopher Parker.

Johannes Vermeer. Faith, Light and Reflection, 2023, Gregor J.M. Weber

https://www.miffy.com/about-miffy

Dick Bruna, 2017, Kjell Knudde, https://www.lambiek.net/artists/b/bruna_dick.htm