[Written by Miriam Simanowitz (she/her)]

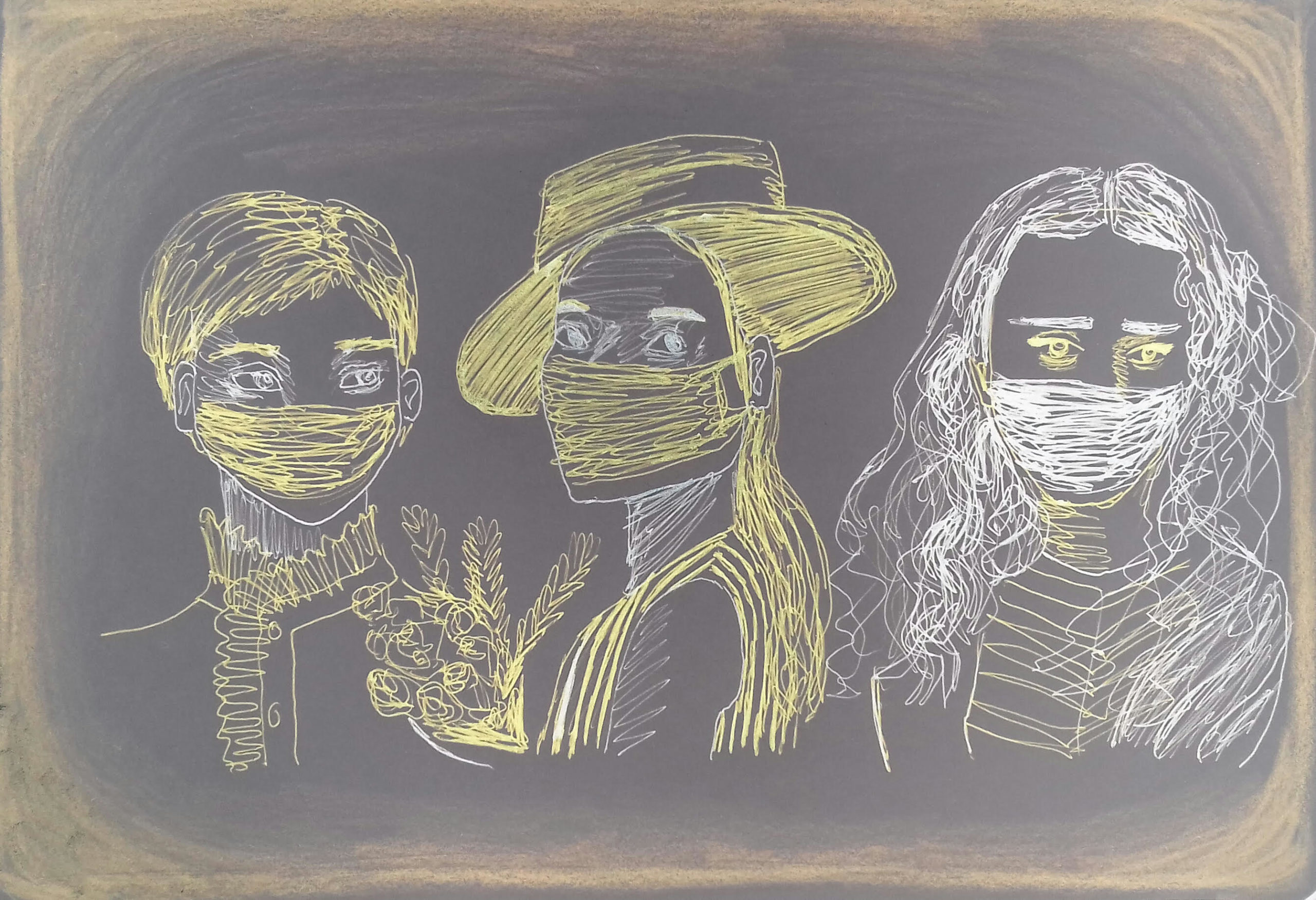

[Art by Anastasia Nevarez-Pyrkova (she/her)]

Content warning: discussion of religion and race

As summer comes to an end, I start donning my trousers and jumpers in place of my summer dresses and skirts; I realise I don’t get the same feeling I usually do when autumn calls for this change. Usually, there’s some sense of relief involved in being able to transition into more warmth/comfort-geared apparel. I can’t deny that I love wearing summer clothing and baring my body to the sun and Vitamin D but, as I’m sure all women can agree, it comes with the drawback of feeling overly self-aware, being sexualised, and sometimes even endangered.

This year, the jumpers in my cupboard aren’t as appealing. As I reflect on my summer experiences of feeling visually sexualised, I realise they have felt fewer and less significant than before. I can think of various points at which I have received unwanted attention from men over the warmer months, but they didn’t particularly bother me. The idea that ‘if you can’t see my face, you don’t know my story’ feels particularly pertinent here, because there has been a new addition to my wardrobe this year, the face mask.

Face masks have become part of everyone’s day-to-day lives during the Coronavirus pandemic and there is now a fine of up to £100 for non-compliance with the face covering rules. The idea that only a few months ago nobody wore them, seems almost unfathomable. A person in a facemask used to stand out as an exception, now the reverse is true. Masks have become intertwined with our everyday, and undoubtedly, a necessary step to stop the spread of the virus. Despite that, they can still be a bit of a nuisance – ‘they mess up my lipstick’, ‘they mist up my glasses’, or ‘no one can see my perfectly groomed moustache now’.

Personally, I feel comfortable with and increasingly drawn to the idea of wearing a mask, even on a more permanent basis. Wearing a mask makes me feel protected from the male gaze. It makes me feel more confident and assertive. It’s a funny juxtaposition because my body can be on show; my legs out, my neckline low but as long as my face is covered, I feel powerful.

Why should covering your face make any difference? Perhaps it is the fact that your face is used to identify you – it’s the place where you show expression and emotion. The uncertainty and anxiety I feel as a result of getting unwarranted attention from men always manifests itself on my face, and I often find it difficult to know exactly which contrived expression I should contort my face into. Do I smile winningly? Or should I frown? Grimace and try to scare them off? Blow a kiss? Stick out my tongue? Say something to them outright? Or maybe just put my head down, avoid eye contact, and walk past as quickly as I can. I’ve tried all of these. And there’s no right or wrong way to act; you have to do whatever makes you feel the most comfortable, the least threatened.

However, by covering your face – the inlet into your true, emotive self – it takes away all of this uncertainty. It takes away the feeling that the right or wrong way to act is in your hands. It removes you, the recipient of the male gaze, from the role of the agent. It reminds you that you are not doing anything wrong by wearing what you want to wear, walking how you want to walk. It removes the feeling of guilt at being at the receiving end, stops you from holding yourself accountable.

The idea of covering your face for privacy, and thus power, is not exactly a new idea. The hijab has been worn by Muslim women for centuries. In its traditional form, it is worn “to maintain modesty and privacy from unrelated males”. I spoke to Aisha Murray, known as @thescottishrevertteacher on Instagram, who converted to Islam in adulthood. She told me that amongst other reasons, she chose to start wearing the niqab as “practicing modesty, it is something [she] find[s] comfort and practicality in”.

Despite the fact that facial coverings, especially in a religious sense, are anything but a recent development, the West has not always been supportive of those who chose to wear them. Thus, my privilege as a white, non-Muslim woman, comes into play here. I have the ability to view my usage of face masks either from a perspective of male-gaze protection or a medical sense (coronavirus transmission). For me, neither of these will inspire ostracisation or social judgement. Regardless, Islamophobia and racism completely change the perception of facial coverings, such as for Muslim women in the UK. To put it simply: my privilege allows me to wear a face mask and not be discriminated against for it. This is not the case for everyone.

My conversation with Aisha made me wonder whether this period of facial coverings has made people more understanding of this element of Muslim culture which has long been a source of tension and opposition. The mandatory use of face masks in France has underlined the hypocrisy in French law of “La laïcité”; the secularity law which bans facial coverings in public spaces. Women were forced by the police to remove their clothing after wearing burkinis on the beach in 2016, yet the same government now requires every citizen to wear a mask. A poll in May found that 94% of French people supported wearing masks but in 2019, 70% of the French public were found to be in favor of banning all religious insignia, including facial coverings. Despite the obvious hypocrisy, France confirmed in May that the face coverings ban of 2010 would stay in place, though the justifications for them – i.e. being a security threat – have now been completely undermined.

I asked Aisha how she and others in her community felt about the double standards behind face masks versus the burka. For governments “saving [Muslim women] from oppression (through making it illegal to wear the burka) by oppressing us doesn’t make sense”, responds Aisha. She continues, saying that “hopefully the continuation of face coverings during and after the pandemic will show people that a face covering is nothing more than a bit of material”. Perhaps the continued use of face masks will see non-Muslims becoming more aware of this hypocrisy behind both de jure and de facto rejection of religious facial coverings.

Widespread use of face masks has certainly opened up a new way of thinking and perhaps even dressing. But, returning to a personal (and non-religious) level, I can’t help but wonder whether taking my ‘modesty’ into my own hands is a good thing. This question reminds me of the five years I spent in an all-girls private school in Central London (a place which celebrated itself for being forward-thinking and feminist). We would regularly line up so a teacher could measure how short our skirts were. If they were too short, we were given some sort of reprimanding on the basis that short skirts would ‘distract the male teachers’. The supposed sexual appetites of the male teachers had therefore been made the responsibility of a group of 12 year-old girls.

It seems that either way women are punished and persecuted for the choices they make with their clothing. 12 year-old school girls are told off for showing too much skin, while Muslim women are ostracised for showing too little. Wearing a face mask changes how I feel when I’m out in public, and I might even choose to continue wearing one in the future for this reason. Nonetheless, the problem remains that I, as a woman, have to literally cover my face to feel this way. That still places responsibility in my hands, when the thing that really needs to be addressed is the judgmental nature of our society in regard to women, and namely the male gaze itself.