[Written by Anna J Reiser]

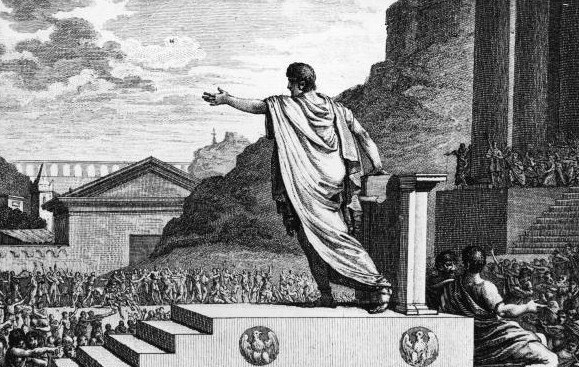

[Image Credit: – Figures de l’histoire de la république romaine accompagnées d’un précis historique Plate 127]

This piece was originally published in the Distractions issue.

In December, Scotland’s leading political publication, Holyrood, produced a front cover with a photo of Steve Bannon and the line ‘Blue Collar Bannon’ emblazoned on it. This editorial decision was much derided, as it was seen to be playing into exactly the image that Bannon wishes to project; that of the little man, speaking up for the hard workers in this changing world. In the Holyrood piece, Bannon is quoted at length; given space to lay out his argument in a reasoned way, without being called up on some of his more dubious bedfellows. The week before the interview Nicola Sturgeon refused to share a platform with Bannon by boycotting a conference. This brought its own criticism as she appeared unengaged with “current ideas”, having thoroughly rejected a wave of populism.

Populism can be a nebulous term, based around the idea of “the people” versus a nefarious elite, it is expandable across the political spectrum. There is no denying that right-wing populism in particular is having a moment worldwide. Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, Nigel Farage, and Marie Le Pen are all capitalizing on populist movements; but where did these figures come from? How does media coverage give oxygen to these ideas, and why is right-wing populism so, well, popular?

Each of these populist actors claims to represent an alternative to the ‘elite’. Trump promised to “drain the swamp”, Bolsonaro’s predecessor Lula da Silva was jailed for a corruption scandal, and UKIP’s rise came in the wake of the MP expenses scandal. In their respective countries, trust in politicians and the political system was at an all-time low. Not least because the reverberations from the 2008 financial crisis are still being felt. It’s harder to have faith that the people in charge are doing a good job, when your life itself feels markedly worse. The irony of course is that every single one of these figures is fully ensconced within the social elite. Farage and Bannon are both ex-bankers, Le Pen is part of a political dynasty, and Bolsonaro was a senior officer under a military dictatorship that he has described as being “glorious”. So, what do these figures add to populism? In his interview with Holyrood, Bannon answers this question with his “theorem”: “You put a reasonable face on right-wing populism and you get elected.”

Central to populism is the seductive idea that there are simple solutions to complex issues. When these ideas are articulated from an authority figure—peripheral to the elite, but distancing themselves from it—they carry power. James Meek characterised the power of a simple story in an article about Brexit that contrasts two myths of Britishness; Robin Hood versus George and the Dragon. In Robin Hood, change comes through continuous redistribution of wealth from the rich to the poor. In George and the Dragon, people are terrorised by a dragon, George slays said Dragon; everything is better! A much punchier narrative. Brexit succeeded in part because it was able to rally around a triumphal moment of “Independence Day” and posit a villain who could be removed.

Unfortunately, right-wing populism is exclusionary; “the people” don’t represent everyone, but an in-group, based on nationhood and race, and the “dragon” is often characterised as immigration and threats to a national culture. In a fast news cycle, populism has the upper hand in terms of story, and therefore press coverage, when simple, sound bite solutions are offered to a nation’s problems. When the alternative being presented is complex, technocratic policy that even politics wonks struggle to keep on top of, news channels will pick ‘build a wall’ for the headline, even if critiquing it. This was reflected in the 2016 election, where Trump received double the coverage of Clinton, although 77% (depending on the moment of the campaign) was negative in tone towards him. It seems that there is some truth in “all publicity is good publicity”.

Should the media interact with an ideology that is discriminatory at its heart? Is the alternative of no platforming effective or does it feed perfectly into a narrative of elites silencing “the people”? The Holyrood interview with Bannon may have been in depth and with the very best of intentions, but by publishing a cover that equivocates Bannon and the working class, and using pull quotes such as “we are on the right side of History”, his position is legitimised as part of the mainstream political dialogue. The Overton window shifts, and people are emboldened to hold and act on discriminatory views.

There is real poverty in prosperous countries, with food stamp usage in America rising to a high of 47.6 million people in 2013. That’s 47.6 million people in the richest country in the world who can’t afford to feed themselves. Last month the UN’s rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights declared that levels of child poverty in the UK were “not just a disgrace, but a social calamity and an economic disaster”. The report also talked about poverty as a political choice that imposed “punitive, mean-spirited, and often callous” cuts in the name of austerity.

You can see why a redemption story of “taking back control” or “MAGA” might be tempting when life is a daily struggle. If we have learnt anything from Trump, Brexit and Le Pen, it’s that it is not enough for the press to regurgitate the sound bites of populist leaders, even if opposing them. Reporting on a story is what journalists do, but it is essential that the excitement of a simple solution and the energy it garners doesn’t simply fan the flames of right populism. Equally it is time for those who oppose the anti-migration wave to start telling an equally compelling story, one where the “dragon” is not the most vulnerable people in society.

[Image Description: A black and white illustration of Roman Tribune Gaius Gracchus addressing the Plebeians at the forum in Rome. The Image features Gracchus standing on a plinth with stairs in the foreground, with his arch reaching out towards a crowd in the midground where there are also buildings in the centre and pillars towards the right of the image. In the background, there are a series of hills, and an aqueduct visible.]