[Written by Anna Rieser]

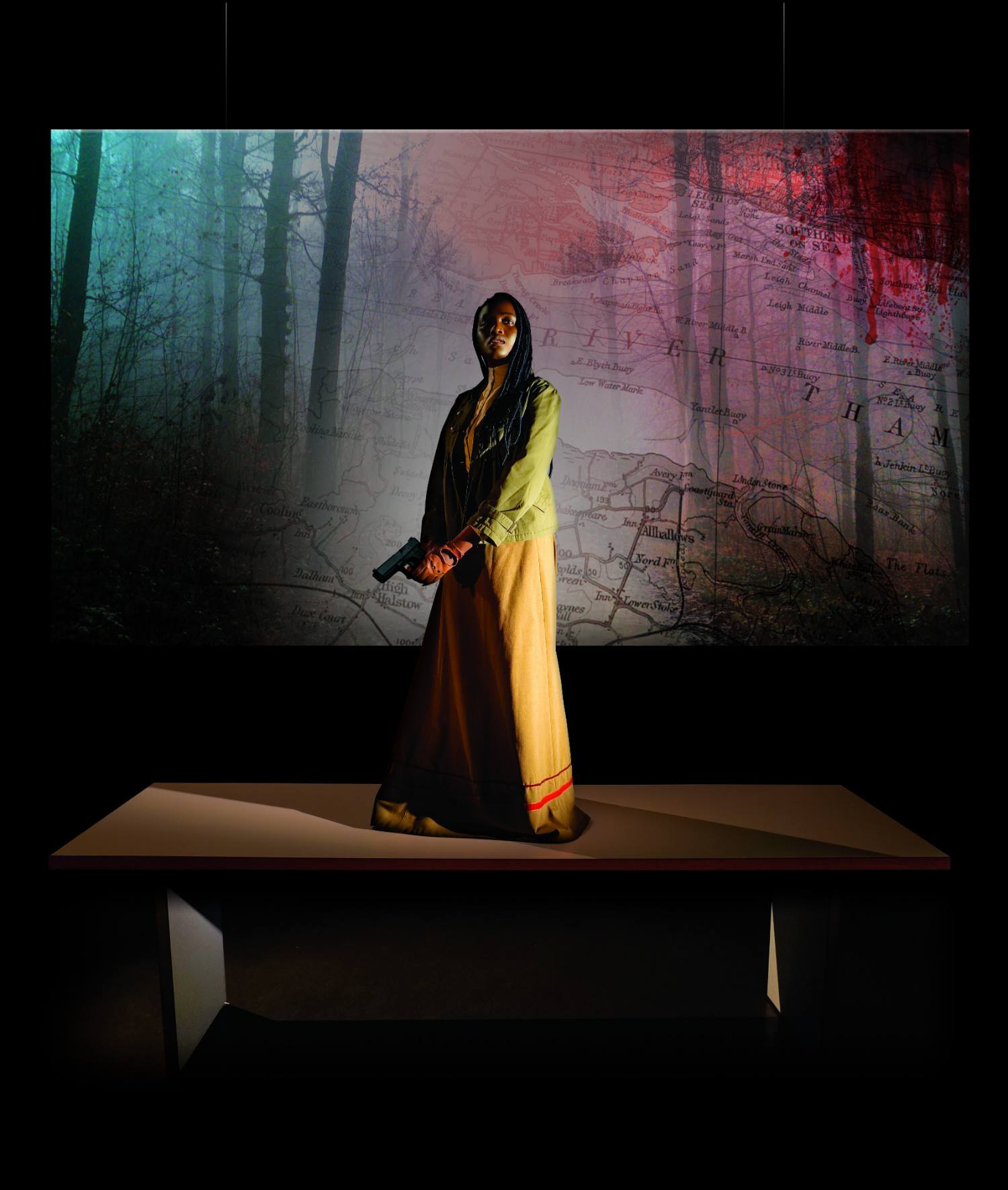

[Image Credit: Imitating the Dog]

In imitating the dog’s new production of Heart of Darkness, they rip apart the story, lay its entrails bare, and splice it back together to create a culturally relevant tale, just as bleak as Joseph Conrad’s.

When working out how to stage a version of Heart of Darkness, the cast and crew of imitating the dog found themselves confronted with the question of “How do we tell this story now, in 2019?”. As a text that both addresses and reinforces a colonial narrative, the novel is nothing if not problematic to a 21st-century audience. The answer that the company came up with is in equal parts ingenious, complex, and contrived, blending digital storytelling with traditional staging, and flipping the narrative so that Kinshasa is a city of light, and London an ominous place of gloom in a lost Europe.

The story is told through three screens at the top of the stage. These are linked to cameras that the actors man, allowing them to have cinematic control so that the screens tell the edited version; a kind of director’s cut. Narrators give directorial instructions; ‘cut to marching boots’, ‘cut to a close up of Marlow crying’, which allow you to imagine the space as a hybrid of stage and screen.

The screens also act as a framing device; just as Conrad’s tale is told through a narrator who recounts Marlow’s tale about Kurtz, here we have several layers of perspective happening simultaneously. You are aware of the craft of storytelling at work as stylistic choices flit from a noir graphic novel; all red light and smoke, to a naturalistic dissection of canonical literature. In doing so, a hyper-awareness of gaze becomes central to the plot.

The audience is shown the decision making process of how we have ended up in Europe, with London as the heart of darkness. The actors imagine the conceit in front of us; Europe as a perpetually fractured continent where the camps established in World War II remain, and inmates are forced to produce materials as the purest form of capitalism; a desire for profit above all else, has eaten any ideology. European hubris has circled back on itself and become an ouroboros that devours the people and land in its path.

The protagonist, Marlow, is a white, British male sailor in Conrad’s rendition. In this retelling he is Charlie, a female private detective from Kinshasa, a city of glass and wealth, whose inhabitants buy the goods produced in Europe. This gender switch is discussed at length; what does it means for a woman to play this role? and does it shift the perspective too far from the original? Eventually, the women of the cast win the argument and Keicha Greenidge takes the part. She slips skilfully between American accented detective and northern English cast member, bringing a new angle to the character.

Throughout the play, images from Apocalypse Now, Blade Runner and Chinua Achebe’s essay Image of Africa flash up on the screen, punctuating the plot with moments of context, reasserting the questionable cultural legacy of Conrad’s novel. There are brilliant moments as Marlow travels on her journey across Europe, where the othering of Africans that Achebe points to in his essay is applied to Europeans. Drinking vodka is made strange, and the food on offer is treated with the scepticism reserved for cannibalism in Heart of Darkness. Even London drizzle becomes hostile and sinister as it is recontextualized. If the purpose of art is to ‘impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known’ as Shklovsky claimed, then throughout the play the audience is challenged and made to reassess the familiar.

There is one moment where the delicate balance of self-reflexivity topples from show to tell. The cast begins to sing Land of Hope and Glory to a backdrop of far-right protests, royals and Boris dangling from a high wire waving union jacks. It is not that the content is inaccurate, it just teeters from making the audience do the work to telling them explicitly what to think. Allusions are drawn throughout the play to the current political moment, with the rise of Tommy Robinson, the Alt-Right, and Trump as a possible path to the state of Europe we see on stage, but it works best when this work is done implicitly.

At the beginning of the play, the cast discuss how the only way to tell the tale is through a radical reimaging, they acknowledge that it ‘might be pretentious but we have to try’. I came away thinking of all the reasons it shouldn’t have worked, and yet this ambitious, bold, and structurally complex retelling triumphantly uses digital technology to create an unforgettable work that locates darkness in all of us. The production continues to tour the UK, catch it if you can.