[Words by Bianca Callegaro (she/her)]

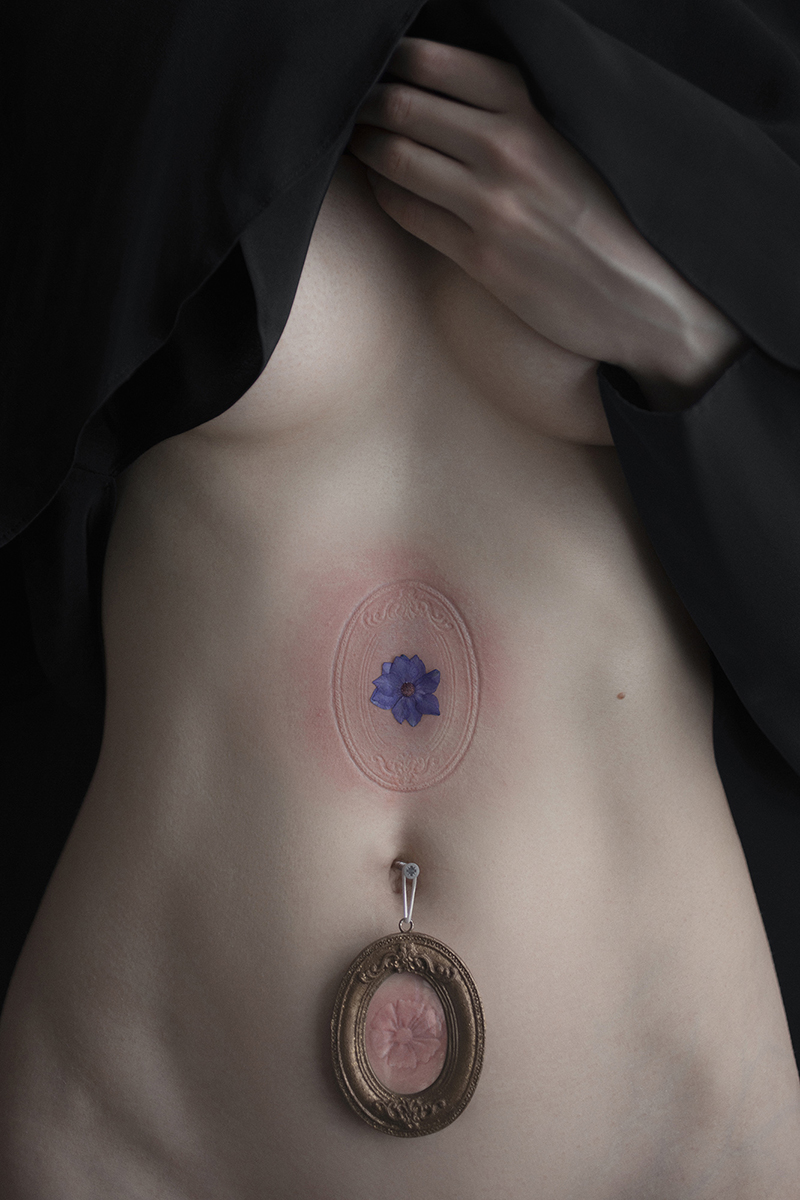

Iness Rychlik is a Polish-born self-portrait photographer who specialises in conceptual art. Although greatly influenced by historical drama, her work is also highly personal and symbolic, as she suffers from a hyper-sensitive skin condition. She uses her skin as a canvas for self-expression to explore themes of solitude and objectification, in the aim to transform hidden pain into art.

To start off, can you tell us about your evolution as an artist?

Looking back at my artistic journey, I can see a rather long and twisting path, as I would often shift between the still and the moving image. While I remember taking my very first photograph at the age of three, as a very young child I was mostly obsessed with my grandfather’s old video camera and capturing the family events. I wrote little screenplays and filmed my Barbie dolls in various scenarios. However, photography became a dominant part of my life in my early teens. Inspired by the classic nineteenth-century novels and their screen adaptations, I began re-creating movie stills in my photography work, which led me to create my own visual stories. Pursuing a Film degree in Edinburgh – such an atmospheric and historical place – seemed like the perfect choice. In my final year, I wrote and directed my own short period drama ‘The Dark Box’. Set in the 1860s, it is a story of an unhappily married young woman, who pursues photography to escape from her oppressive relationship. ‘The Dark Box’ premiered at Camerimage, where I received a Golden Tadpole nomination for my cinematography. However, for the past two years I have been focusing on my conceptual self-portrait photography.

How would you define your style? How did you develop your own artistic voice, and what inspired you?

I describe my style as conceptual erotica, vastly informed by my own difficult experiences and my long-lasting fascination with nineteenth-century Britain. I find the Victorian Era so paradoxical – it is a period of rapid technological advancements, and yet social progress was so slow and painful. A woman was a lower-class citizen, with very few laws to protect her – in the higher spheres, she would serve a purely decorative role. I often use antique garments or props to depict the parallels between my experiences and the inferior female position in Victorian Britain. The most prevalent themes in my work are solitude and objectification.

Your photographic work consists mainly of conceptual self-portraits which reflect on and originate from your skin condition. How do you justify your predilection for this specific genre? How does your personal experience come across in your photographs?

My self-portraits are deeply rooted in my personal experiences. However, I did not experiment with my skin condition much in the very beginning – it is a direction I was able to fully embrace once I gained more confidence. Through art, I have learnt to transform my hidden difficulties into something beautiful and visible. Even though my imagery is dark, the whole creative process brings me incredible joy.

We’re living through a time in which the fragility and impermeability of bodies appears even more apparent. How do you use photography to explore the body? Is it to reflect on its vulnerability or to affirm its power?

Photography allows me to reflect on both my physical and psychological vulnerabilities. Whether one is dealing with mental trauma or a perceivable disease, being able to express it in a productive and creative way comes with a great sense of relief. Ultimately, it is a deeply empowering experience.

Through your art you make use of your own body almost as if it were a canvas, nonetheless without showing your facial features. How should this be interpreted?

My self-portraits are often headless, as I believe that using my body rather than my facial expressions is a more imaginative way of depicting emotions. Moreover, it allows my audience to identify with the subject and the feelings I portray.

As a female artist, what reactions do you want and expect to trigger in the viewers looking at your photographs?

I invite the viewers to look at my photographs through the lens of their very own experiences. It makes me happy to see so many people engaging with my work, sharing their interpretations or even personal stories. I am not oblivious to the fact that the erotic genre might attract some unwelcome attention. However, the vast majority of my audience appreciate that I want to portray the female form in a more captivating way than the sexist images we are flooded with on a daily basis.

Let’s talk about your creative process. How do you go about creating a new project? Do you experience creativity bursts and on-the-spot inspiration or do you “research” and develop your subject for a long time before starting?

Bursts of inspiration are wonderful, but I firmly believe that an artist must continuously work on their creativity. On a practical level, this approach involves a lot of research, prop-hunting and painstaking test shoots. I do not force myself to come up with new ideas right-here-right now, but it does not mean I will wait around for a mythical muse to grace me with her presence. By continuously exploring different art forms, I try to cultivate the right climate in my mind, where ideas can grow and flourish.