Words: Kiyara Thring she/her

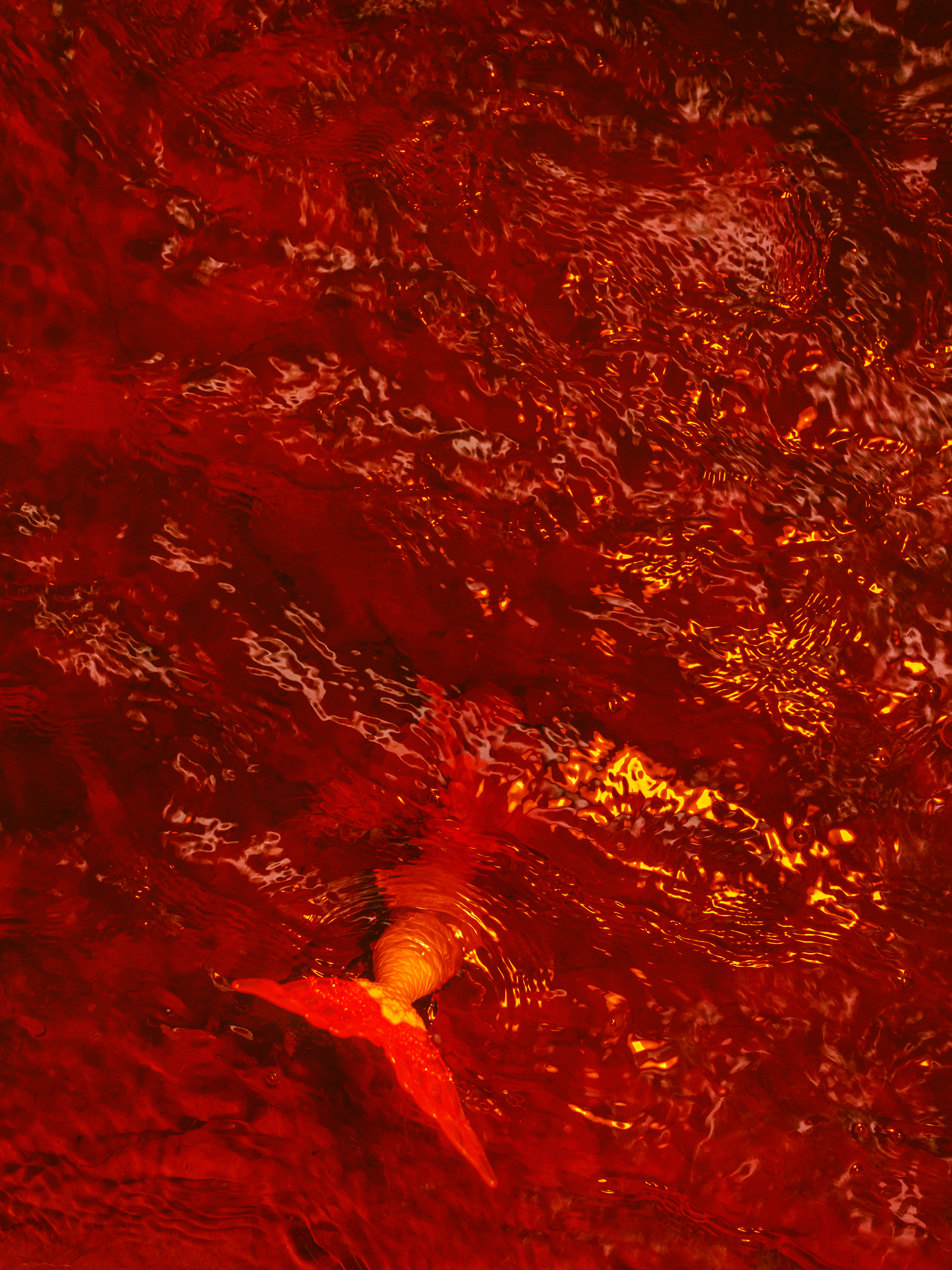

Artwork: Joanna Stawnicka

“Ariel, listen to me, the human world, it’s a mess.” It’s 2022, and the importance of identity representation in visual media is still a debate – I’d say ‘mess’ is accurate.

Thirty years have passed since the debut of The Little Mermaid and in true contemporary Disney fashion, the production company has spun out yet another live-action remake of an old classic; immersing a new generation in the world of under-the-sea fantasy. In 2019, Disney announced that R&B artist – Halle Bailey had been cast as Ariel. Given that the only black Disney princess to ever grace our screen was Anika Noni Rose when she voiced Tiana in 2009, many were quick to praise the importance of a black woman portraying Ariel and what this represents for children of underrepresented communities. Conversely, some of us were left nonplussed by the predictable, tiresome, and almost humorous inevitability of opposing opinions of ignorant individuals. Some found it necessary to debate the inauspicious effects a black Ariel would have on the film’s reception – a lost cultural nostalgia and not to mention the unspeakable biological and scientific inaccuracies… about a mermaid and singing fish?

Disney often receives backlash and intense criticism on their classical remakes. It is no secret that the films are heavily embedded into generational culture and, with that, comes a pressure to ‘do them justice’. When the trailer for The Little Mermaid (2023) premiered it was characterised by negative responses with 1.5 million dislikes on YouTube and the #notmyariel trend plaguing Twitter. Perhaps most bewildering was not the negative criticism and social backlash, but rather the public display of audacious and unadulterated racism, specifically from grown white males. Political commentator Matt Walsh has been a circling name in this ‘controversy’ since stating:

From a scientific perspective, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to have someone with darker skin who lives deep in the ocean. I mean, if anything, not only should the Little Mermaid be pale, she should, actually, be translucent.

Additionally, CGI and AI cognoscenti have gone on to edit and modify the trailer changing Bailey’s skin from black to white with the aim of “fixing” the accuracy of the film. Olive Pometsy put it best:

You can’t reason with a racist. Because if there’s anything that lacks sound rationale, it’s deciding to hate people who look different to you so much that you’ll spend your time creating a revised CGI rendering of a film aimed at seven year olds.

I couldn’t agree more. It seems rather frivolous to be discussing the melanous exactitudes of marine biology as a justification for racial slurs in the same breath as dancing crabs and evil sea witches, and yet here we find ourselves.

Growing up I did not pay attention to the diversity or identity representation in the animated films I was watching. I hadn’t even considered the importance of it all. However, as I introspect, the psychological effects behind the visual image are especially prevalent in my life as a person of colour. At such an impressionable age, visual representations of culture are internalised and manifest themselves in self-image, identity formation and how we place ourselves in society. In 1999 Elizabeth Yeoman investigated the effects of textual and visual exposure on the belief system of children by asking young students to draw the princess they imagined as she read San Souci’s, The Talking Egg:

“I imagined her dark, but I’m drawing her blonde” (p. 437). When asked why, the child said she did not know. A third child said she “drew her yellow [haired]…because. . .she was good, so I wanted to make her pretty” (p. 438).

I have my own vivid childhood memories of drawing my own princesses and reaching for peach-coloured pencil crayons as well or visiting a friend from school for the first time and being shocked by her collection of black Barbies, some with curly hair like mine. Disney’s lack of representation for little girls like me fuelled the continuous and pervasive ideology of perceiving:

“White” as good, living happily ever after, and pretty.

Identity consciousness and celebration is increasing, cinema is not going to look the same as it used to. Many of the stories that we have heard and seen are created from white perspectives, for white identities which tend to nudge us into the white male worldview. This film is culturally ground-breaking and necessary for the progression of cinematic cultures. Tiana’s debut into the lives of children was over 11 years ago (and she spends 90% of the movie as a frog!). These fact spitters and nostalgia culture junkies fail to realise that the children of colour who watched this trailer and shouted, “She’s like me!” are what matter – let the dream world of the Disney princesses be part of their world too.