By Jojo Guo (She/Her)

Content warning: Discussions of death/dying

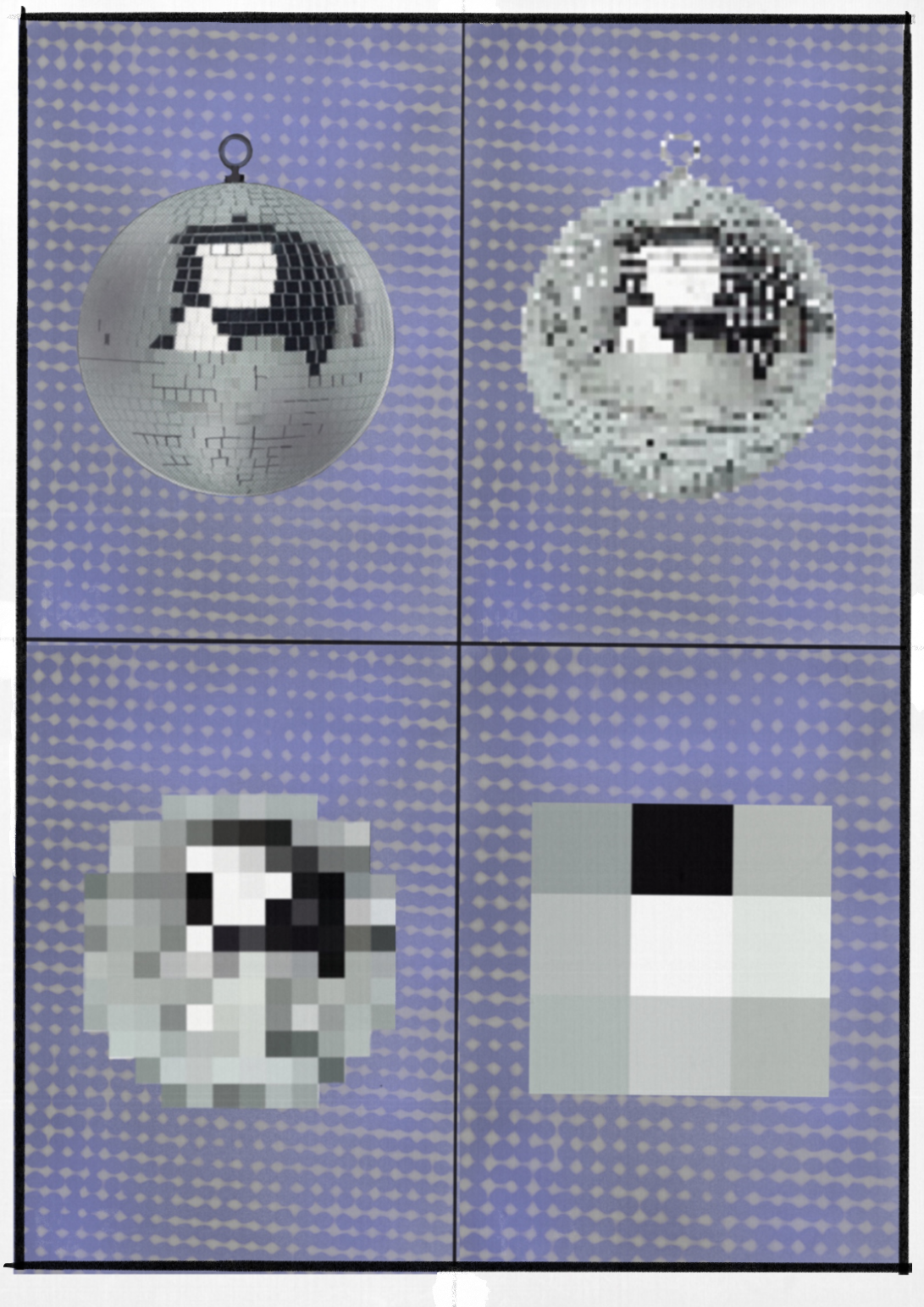

When addressing Posthumanism, the ever so perplexing question of ‘what makes a human human?’ confronts us once again. Technologies including audio recording, digital archiving, photography, film…constitute the ‘Post’ part of the terminology: using modern technological inventions to preserve what was once ephemeral in nature, the human existence in each of its distinctive moments, and allow it to extend beyond our being in pixelated flesh. Humanity, therefore, is the ephemerality, the living in its own history, the unvisitable past relentlessly driving us forward, hence, nostalgia.

The Immortal World Tour and ONE were not successful because Michael Jackson and Cirque du Soleil were a collab overdue, but for the solid fact that Jackson is no longer part of this world, and that the fans have missed seeing him. As humans, our obsession with the past, the no-longer, drove us to be capable of transferring memory into the sense of nostalgia, and arguably, nothing triggers nostalgia more remarkably than music. However, is seeing a hologram of Michael Jackson on stage really as innocent as simply listening to his songs or reviewing his concert documentaries?

Nostalgia, according to the sociologist Fred Davis, can be a way of using ‘positive perceptions about the past to bolster a sense of continuity and meaning in one’s life’; a way of reflecting and thus gaining from this journey of reflection. However, this act of remembering and reflecting exists upon the physical and temporal distance between us in the present, and the object of remembrance in the past; the emotional togetherness we feel when dancing to an all-time-classic is nurtured upon the collective reminiscing of the era during which the song was released, as well as our personal private association with the music. Yet, in attempting to satisfy the fans yearning for old music and dead artists, with hologram performances or the upcoming ‘Abba-tars’, it is perhaps taking away exactly what makes us grow fondly nostalgic of these classics, as they erase the distance between us and the things we miss, exposing us to our memory. More concerningly, following the trajectory of ABBA’s digital return, what is being projected is not even our memory, but the distilled and manipulated result from a database of past footages and photos, an ‘ABBA in their prime time’ that never truly existed but decided amongst the crew and their software, presented to us as an open invitation to believe in an illusion: ‘performing for their fans at their very best: as digital versions of themselves’, stated on the website of ABBA Voyage.

If this is the future of the music industry, and having an Avatar of yourself becomes the next staple of success instead of a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, what does it mean for new emerging musicians? Facing this trend of reviving classics and immortalising dead artists, being young, new and alive seem to be thrown into immense disadvantages. The market, as saturated as it already is, will see another wave of dominion from deceased artists surviving through computers, making a high speed of ‘turnover’ the only possible solution to give space to more artists: each musician racing their life to the goal of one billboard hit, then retire swiftly into a forest of green screens, beholding their virtual rebirth—if they can afford it.

In 2012, the five minute hologram appearance of Tupac in Coachella cost 6 weeks and $600,000. In 2022, ABBA’s grand return will not only introduce the fans to their digital selves created by George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic company—the same team responsible for the special effect of Star Wars—but also a brand new arena in London built solely to provide the best avatar viewing and listening experience. Evidently, the emphasis on being already famous and successful is even reflected in the financial requirement to achieve this level of success. Although, yes, a new artist can theoretically reach that level of artistic success and financial capability through talent and hard work, the dead artists are already making profit from their unseen footage and unreleased songs, which is then shared between their estates, the consultants of their estates, and the big technology companies who will continue to serve dead artists with great capital over grassroot musicians, who struggle to even receive an adequate amount of profit from releasing music on streaming services. In 2012, three years after Michael Jackson’s death, the ‘Immortal World Tour’ earned $160 million in its first leg of performance, an amount so massive that it attracted the IRS into an attempt of suing Jackson’s estate, for earning profit from using untaxed images in the hologram. Despairingly, not only does this profit earned from the post-humanistic mediums within the music industry fail to circulate for the benefits of living and disadvantaged artists, it is often tragically tangled within lawsuits between giant technology companies and the dead artists’ families. Meanwhile, independent musicians write songs between odd jobs, left behind in this race of becoming the next profitable form of nostalgia, a race that perhaps they do not even want to be a part of.

I watched the trailer of ABBA Voyage, and felt strangely touched then an abrupt flood of sadness. Not from the grandness of their return or the musical history they carry with them, but from the movingly insistent yet perhaps futile nature of this step towards eternity.