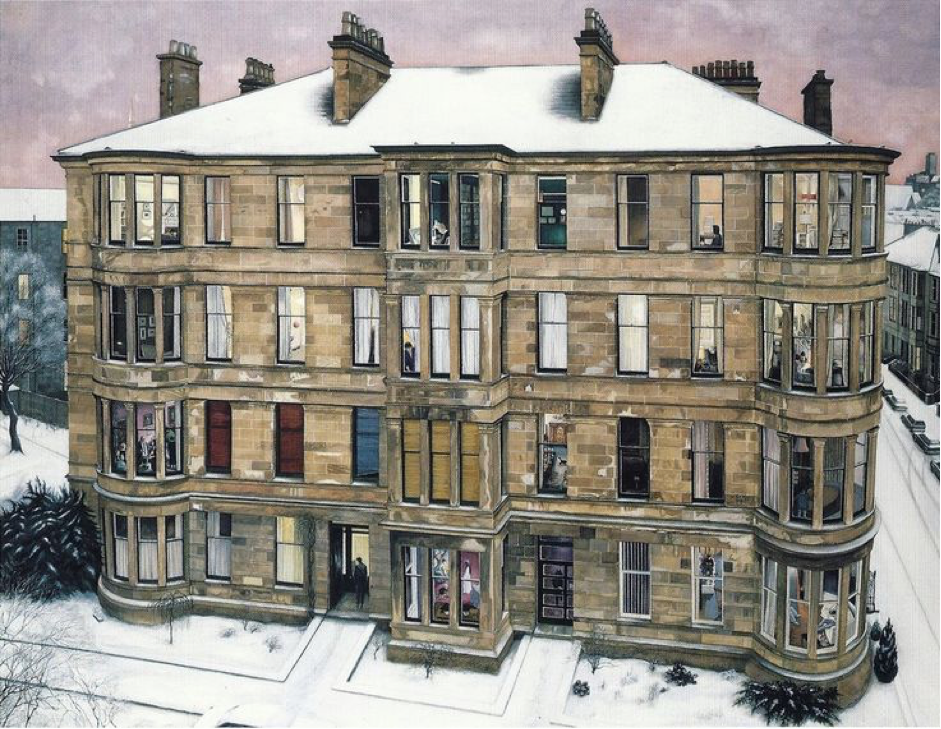

I am now studying Urban Geography, which involves the analysis of the interplay between human behaviour and the (built) environment, and therefore I have a special interest in architecture. The first year of my studies I found out that I was not only interested in the facades of buildings, but also what hides behind the front door. While I was exploring Glasgow, I inevitably entered the Kelvingrove Museum where I walked past the painting ‘Windows in the West’, which perfectly shows my sentiments towards the flats in the city: we all live together apart, and try to make the best of it.

As with almost every city, Scottish architecture differs from the Dutch. Whereas in the Netherlands, buildings are usually built with small bricks, here, in the West End for example, the Victorian houses consist of large chunks of stone. But I found one of the most interesting features of Scottish building practices when I started doing fieldwork for my thesis. This involved posting leaflets in mailboxes to announce my presence in a neighbourhood. I was startled when I found out there are no mailboxes on the outside of closes. Of course, later I discovered that you actually have to enter the close to post anything. This raised some questions, since one entrance to a close had a sign saying not to let in any strangers. The placing of mailboxes outside might decrease the risk of unwanted guests entering.

Apart from the appearance of the buildings, the housing policies and housing stock of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands differ significantly. Whereas in the Netherlands, the social housing stock comprises the majority of the housing market, the contrary is the case in the United Kingdom. The Netherlands is actively trying to decrease the share of social housing. Bearing this in mind, it struck me that the Guardian devoted on the 23rd of September a 15 page long special in their paper to the promotion of social housing. It is strange that both the promotion and decrease of social housing seem to have the same outcome or at least imply that that is their purpose: improved social cohesion.

How can the decrease or increase of social housing improve social cohesion? The idea is that more mixed communities in social, economic, cultural and ethnic terms is fruitful ground for more tolerance from every angle. In short, homogenous neighbourhoods are something that should be avoided. Apart from the fact that mixing could create tolerance, some people argue that different social groups can learn from each other and make bridging social bonds which can help people to advance further in life.

The question is of course if this is actually the case. There is evidence that mixing creates more tolerance and may result in some mirrored behaviour, but other research points out that it tears up local communities when, in the Netherlands for example, social housing is replaced by private rental or owner-occupied housing. The flipside is that deprived areas know a lot of problems, and that interventions have to be made somehow. Whether social mixing is the one and only solution has to be discussed. One of my respondents in the Netherlands said: ‘What if you had done nothing?’. Indeed, a lot of times in these restructured or regenerated neighbourhoods the situation is improved in quantified terms. But often this also means that the ‘problem’ has moved to other or more peripheral areas.

Avril Paton – Windows in the West

Currently in Kelvingrove Museum

By Rosa de Jong