Content Warnings – Drug Use, Alcohol Dependency

Charlotte Hutton, She/her

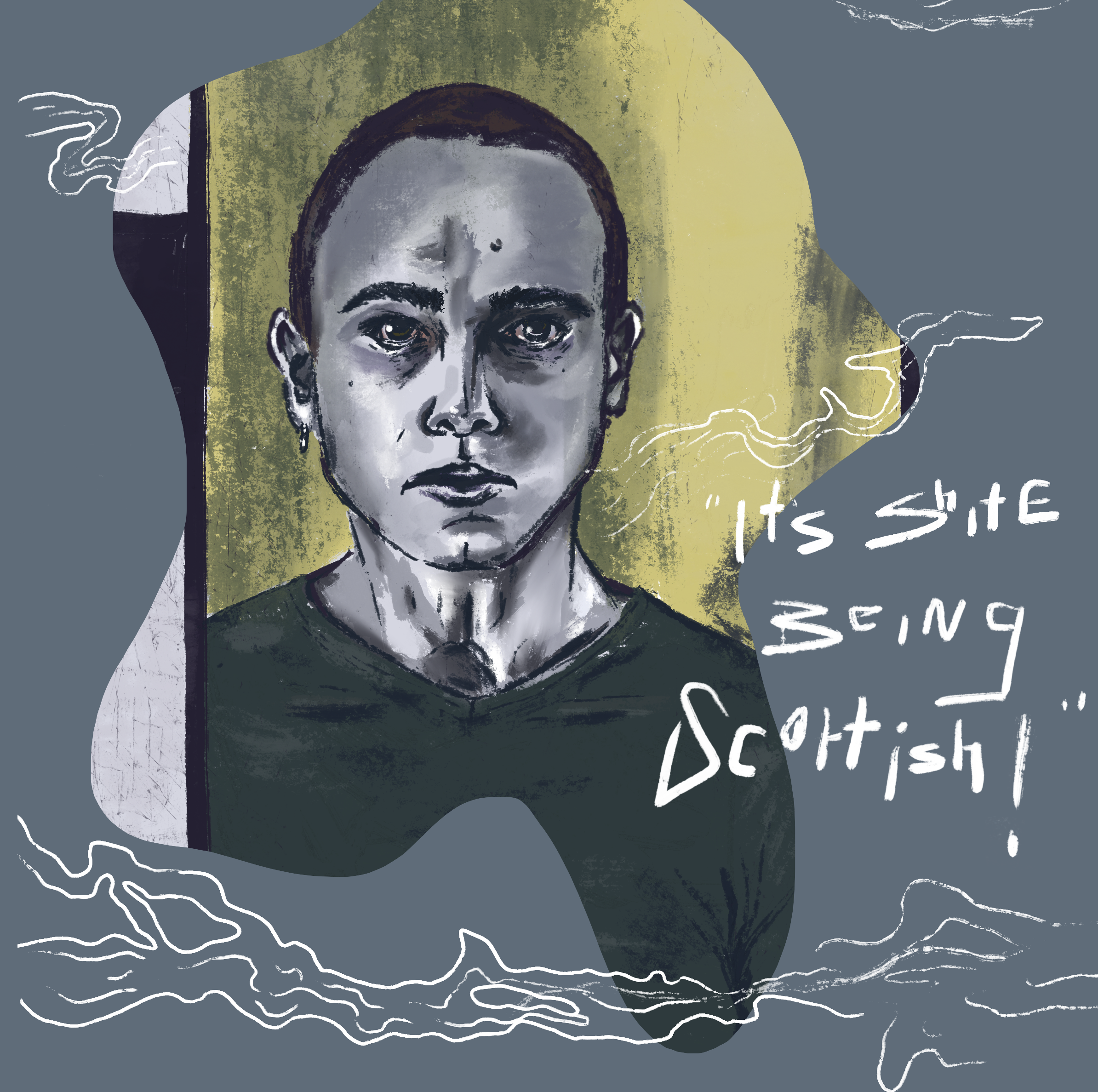

‘It’s shite being Scottish, we’re the lowest of the low, the scum of the f******g earth!’

Aside from his point about being ruled by ‘effete arseholes’, I wholeheartedly disagree with Ewan McGregor’s Rent Boy in his passionate state-of-the-nation outburst, set against the backdrop of the dreich Scottish Highlands in Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996). Although Rent Boy’s good old classic Scottish pessimism makes for one of the film’s most iconic scenes, his anguished admission reflects the grim and gritty realism that Trainspotting came to be synonymous with. Renton and pals Spud, Sickboy, Tommy, and Begbie navigate poverty, heroin-addiction, and HIV in a post-Thatcher landscape. The film was set just prior to the end of the near-two decades of Tory rule, decades which left Scotland with wounds felt deeply by the country’s working class and most vulnerable population. It really should make for grim viewing, but the film’s timeless vigour, humour, and distinctively Scottish lust for life – mixed with a feeling of profound dissatisfaction and disillusion with the divisions of nationhood – make Trainspotting a rich example of a Scottish film that is so particularly Scottish.

More than twenty years after the release of Trainspotting, Brian Welsh’s Beats (2019) arrived on our screens. The film is set in Scotland in the aftermath of the 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act. This act gave the police authority to shut down gatherings with music ‘wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats’: a glaringly marked reproval of the UK’s illegal rave scene. In Beats, Johnno and Spanner are best mates, the latter of whom is denounced as ‘scum’ by Johnno’s middle-class family. The film is a portrait of young male friendship and partying as a form of class protest against a government who wants to ‘privatise our minds’ and ‘keep us in boxes’. Trainspotting and Beats are both stories of young, working class masculinity and resistance set in the mid-90s in the underbelly of Scotland’s nightlife. Renton and Spanner could very much have crossed paths; they are both reckless and disillusioned, feeling left behind by a country that doesn’t care about them. Both films tap into a sense of generational loss felt specifically by young Scottish men in that period, navigating toxic masculinity in an environment in which it is nurtured. But there is something about Trainspotting and Beats that makes them far from downright depressing, something that is indebted to their distinct Scottishness: self-deprecating humour, kinship, and a kind of hopeless optimism you’ll understand if you’ve ever waited outside a chippy on Sauchiehall Street at 4am in the pishing rain.

Your da’s favourite Scottish film is probably Bill Forsyth’s breakthrough feature Gregory’s Girl (1981). Set in suburban Cumbernauld, Gregory’s Girl offers a more gentle coming-of-age story, following sixteen-year old Gregory’s pursuit of Dorothy, who joins his otherwise all-male football team, and whose talent far outshines Gregory’s football abilities. The film has all the ingredients of an 80s high school teen movie: the trope of the awkward teenage boy who is infatuated with the popular girl, but eventually ends up going for the girl-next-door. Yet Gregory’s Girl feels more earnest and nostalgic than any John Hughes classic. Perhaps this is owed to Forsyth casting real Scottish teenagers, with Clare Grogan who plays Dorothy being spotted by Forsyth while waitressing in a Glasgow restaurant. But it’s the familiar setting, dreamy synth soundtrack, and authentic script (chock-full of Scottish colloquialisms) that breathe life into the film, making it stand the test of time as a classic. Forsyth followed the success of Gregory’s Girl with Local Hero, his 1983 film about a Texan oil executive who is sent to the village of Ferness in the Scottish Highlands to buy off the land for a North Sea refinery and ends up falling for the place and the locals. Forsyth’s writing is the kind of familiar and unforced humour that emanates from everyone knowing everything about everyone in an otherwise mundane small-town Scotland. The punchlines feel genuine and unassuming, demanding little from the audience, often taking them by surprise due to their patient timing.

Renowned socialist director Ken Loach, acclaimed for making films centring around social and political struggle, chose Scotland as the setting for many of his stories of hardship.c (1996) is about a Nicaraguan asylum seeker who forms a relationship with a Glaswegian bus driver, whilst My Name is Joe (1998) follows a recovering alcoholic in Glasgow who falls in love with his health worker. Sweet Sixteen (2002) is perhaps one of Loach’s most tender and hard-hitting portrayals of working-class Scottish life, tackling the topic of drug violence and early 2000s Glaswegian Ned culture. The scenes are bleakly recognisable in a classic Loachian fashion; young guys in trackies take centre stage amidst the council estates of Greenock and dismally overcast Scottish skylines. But there is a tenderness and humanity to Sweet Sixteen in which sixteen-year old Liam is determined to get his Mum released from Cornton Vale prison for a crime he’s convinced she is innocent of. Liam is descended from a generation who have faced hardship due to the collapse of industries like shipbuilding. There is a sharp humour that grew from this tragic decline that is noticeably present in the film’s content and language, and firmly embedded in Scottish working-class culture. Set in Glasgow amidst the binmen strike of 1973, Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher (1999) follows twelve-year old James living in a Govan estate during a time of mass unemployment and deindustrialization which consequently resulted in the collapse of social roles traditionally sustaining a sense of male identity. This crisis in working-class masculinity is deeply rooted in the Scotland that James, Liam, Renton, and Spanner are coming-of-age as young men in.

In a sense it is understandable that Rent Boy accuses the Scots of being ‘the most wretched, miserable, servile, pathetic trash that was ever shat into civilisation’. And it is this that is at the root of what makes these films so distinctively Scottish: the self-aware and sharp-witted humour that resists and sustains even despite the shite state of affairs.